YES,THE

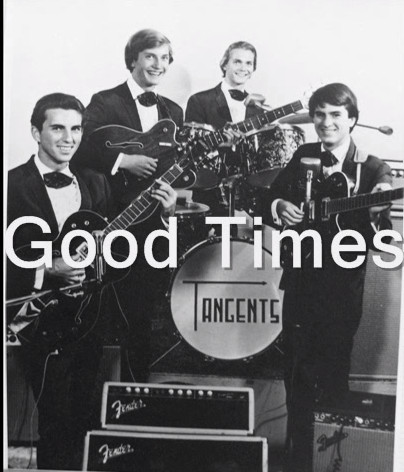

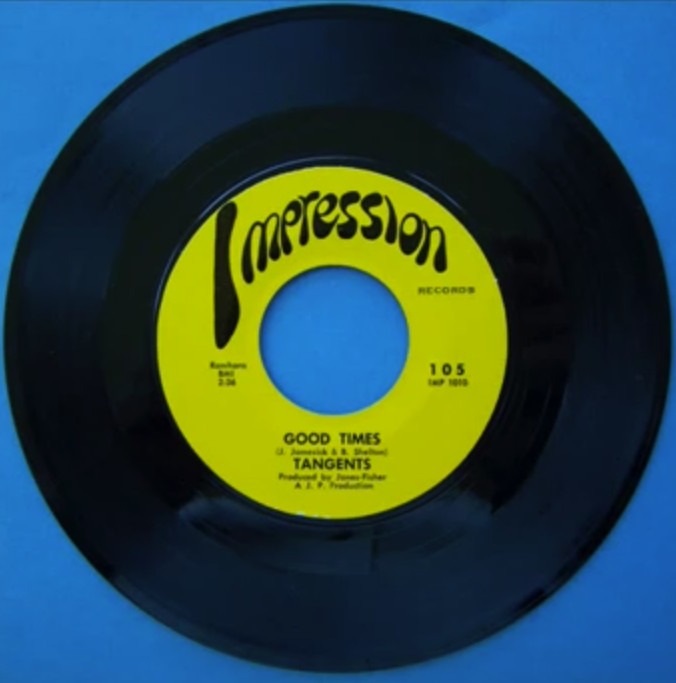

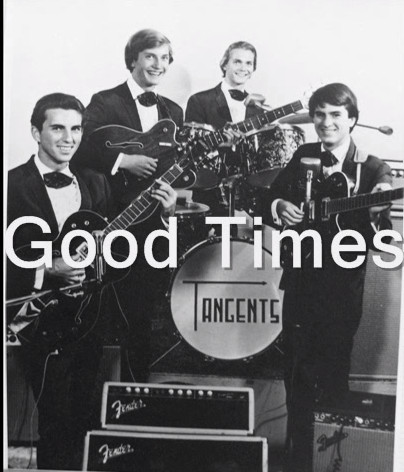

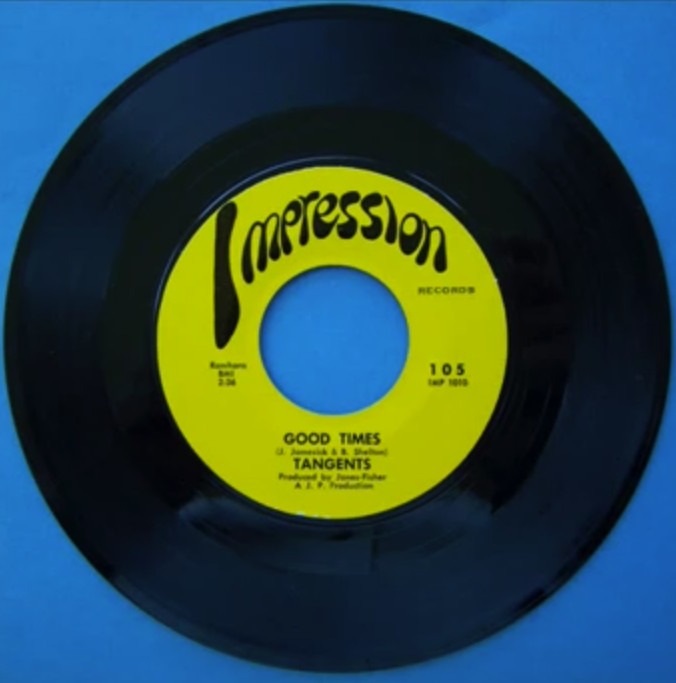

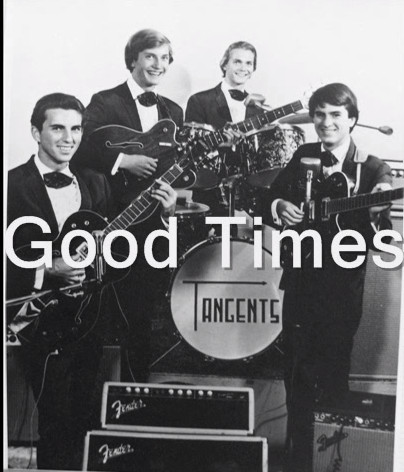

GOOD TIMES AND THE TANGENTS. Janesick did not start his working

career as an engineer, but as lead guitar in the 1965 music

group, The Tangents. The Tangents

recorded four songs in 1965: 2 originals,"Good Times" and "Till I Came

Along" and 2 covers of "Hey Joe" and " Stand By Me". Band members

were: Bob Shelton, lead guitar & vocals; Terry Topolski, bass;

Warren Brogie, drums; & Jim Janesick, lead guitar.

Unfortunately (but fortunately for the world of astronomy), the Viet

Nam war caused the band to break up and Janesick entered Jr.

college to catch up on basic learning not gathered in high school.

After two years transferred to Cal Poly Pomona to receive a BSEE

degree. Later he entered university of California at Irvine (UCI)

leaving with MSEE in lasers and masers. After UCI he was employed

by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) which is operated by the

California Institute of Technology (Caltech) for the National

Aeronautics and Space Administration.

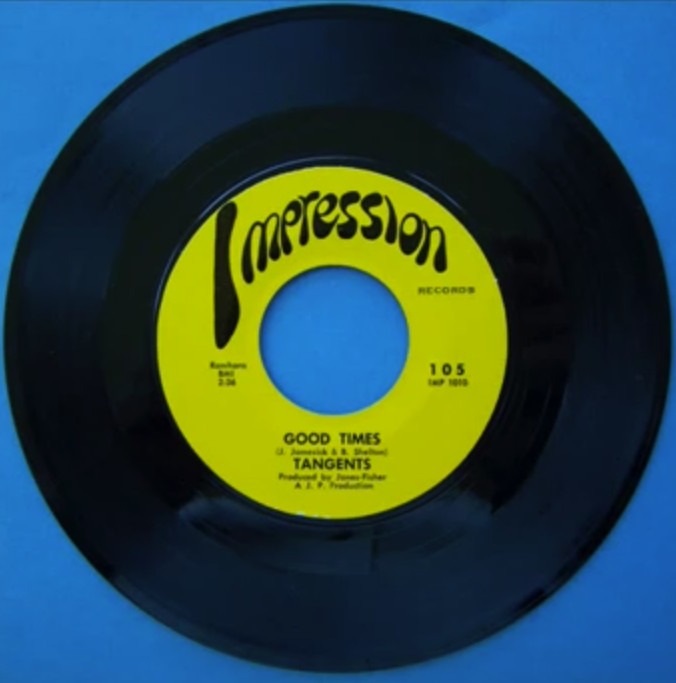

Listen

to a little 45 record music by clicking on the URLs below (for you

younger folks, 45s were small-sized records with big holes in the

middle.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MS_kXiESQTA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hqgmLWtbnGk

"AN APPLE DOESN'T FALL FAR

FROM THE TREE." Jim Janesick's daughter is not only a star

ballernia, but she also has a Ph.D. in molecular biology from her dad's

alma mater, the University of California at Irvine. Top that if

you can!

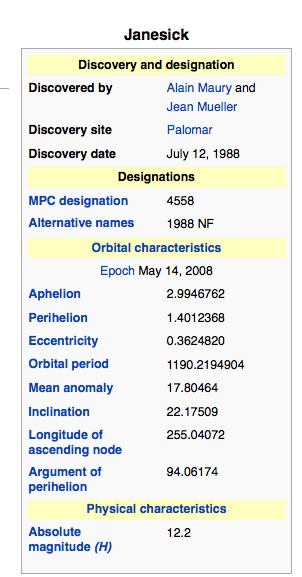

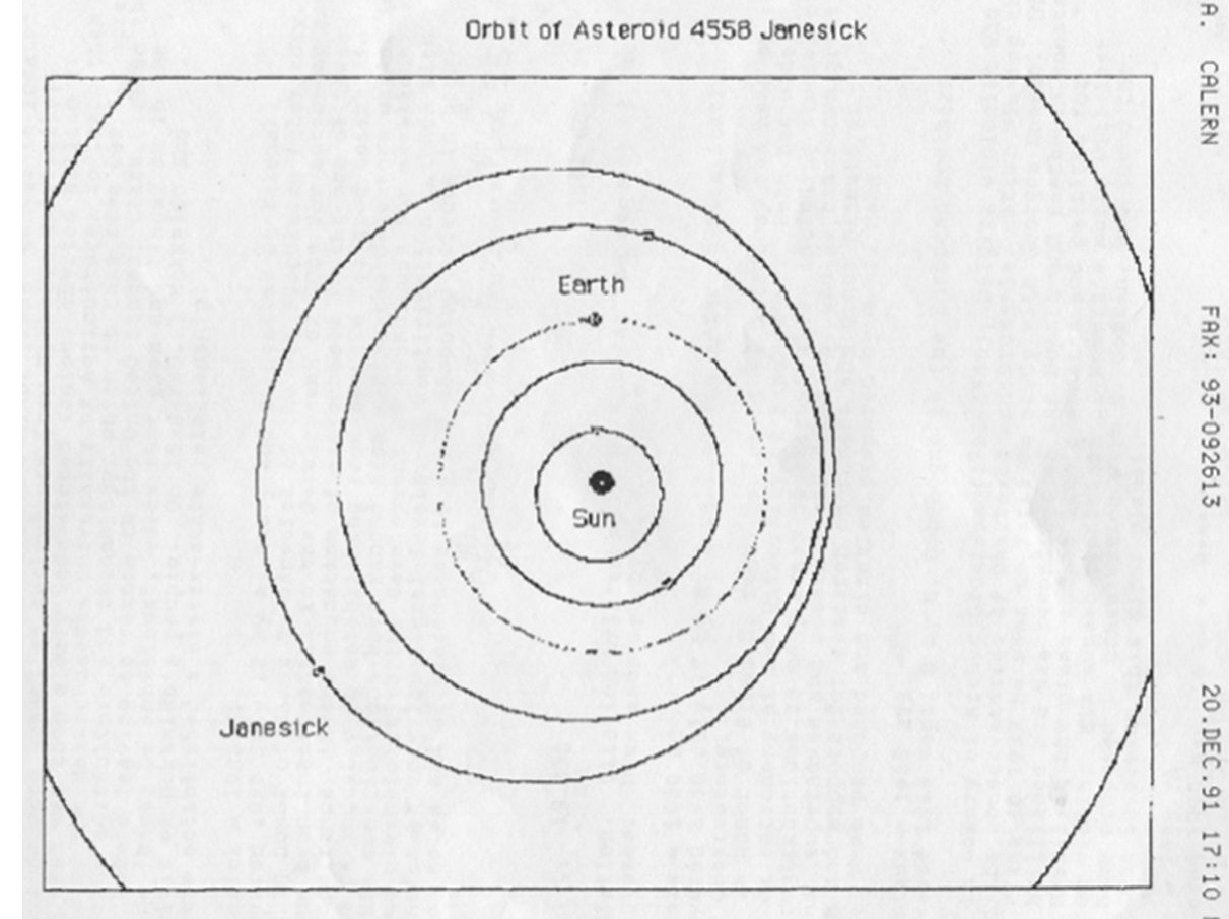

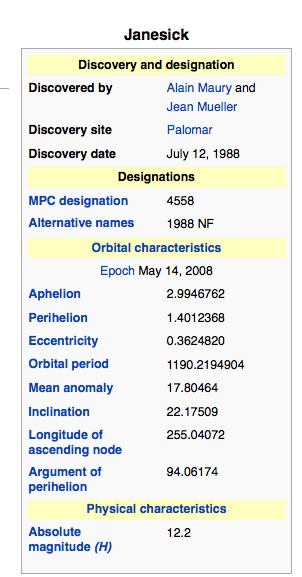

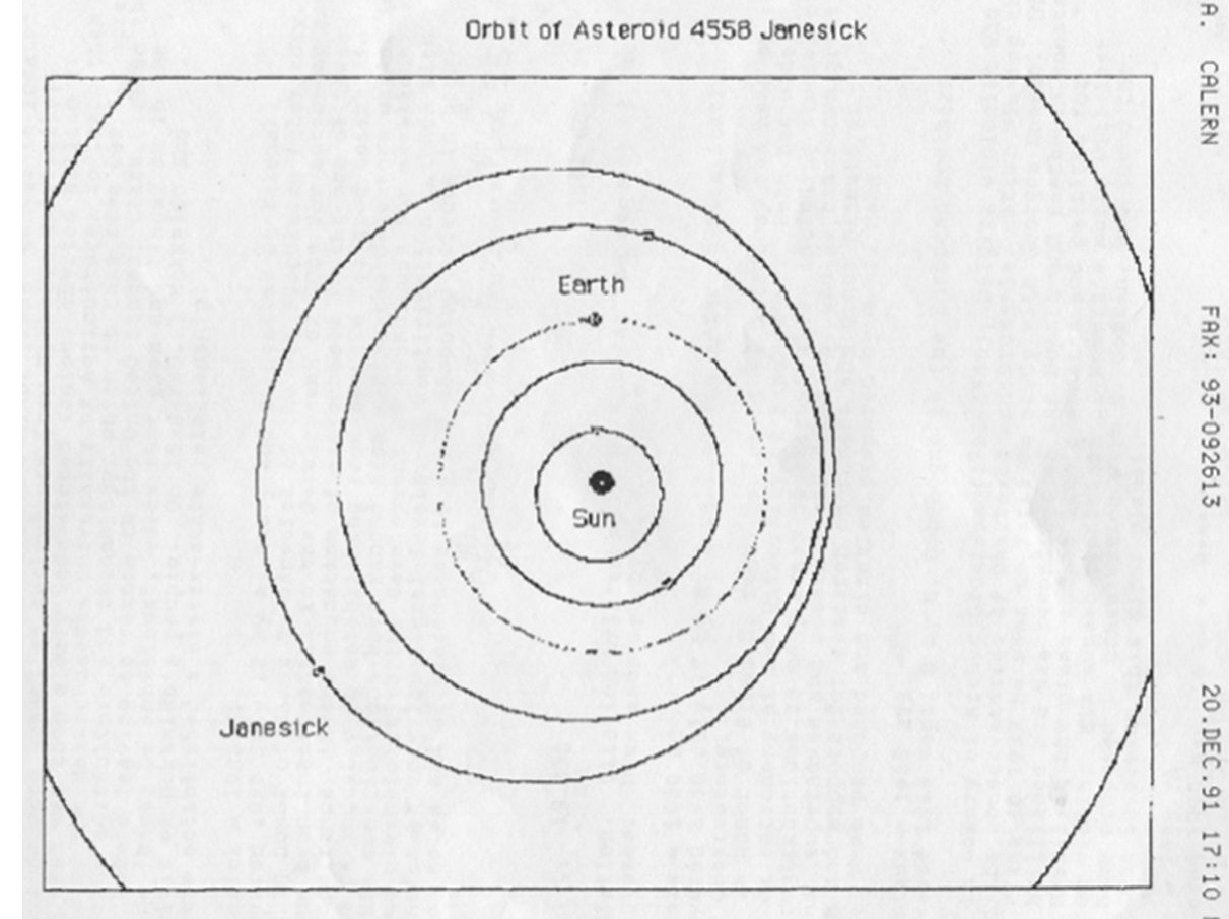

Mars-crossing asteroid named in honor of James R. Janesick

(4558) Janesick

88 NF. Discovered 1988 July 12 by A. Maury and J. Mueller at Palomar.

Named in honor of James R. Janesick of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Janesick has been instrumental in the development of CCDs for astronomy

and, of equal importance, in the education of astronomers in the use of

these devices and of industry in establishing requirements for good

scientific imagers. His contributions have ranged from making the

detectors useful in the blue and ultraviolet to the development of

techniques for excellent charge transfer at very low signal levels, of

amplification methods with sub-electron noise and of procedures to

avoid damaging effects in high-energy radiation. (M 19337)

http://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007%2F978-3-540-29925-7_4491

http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/sbdb.cgi?sstr=4558%20Janesick;old=0;orb=0;cov=0;log=0;cad=0#phys_par

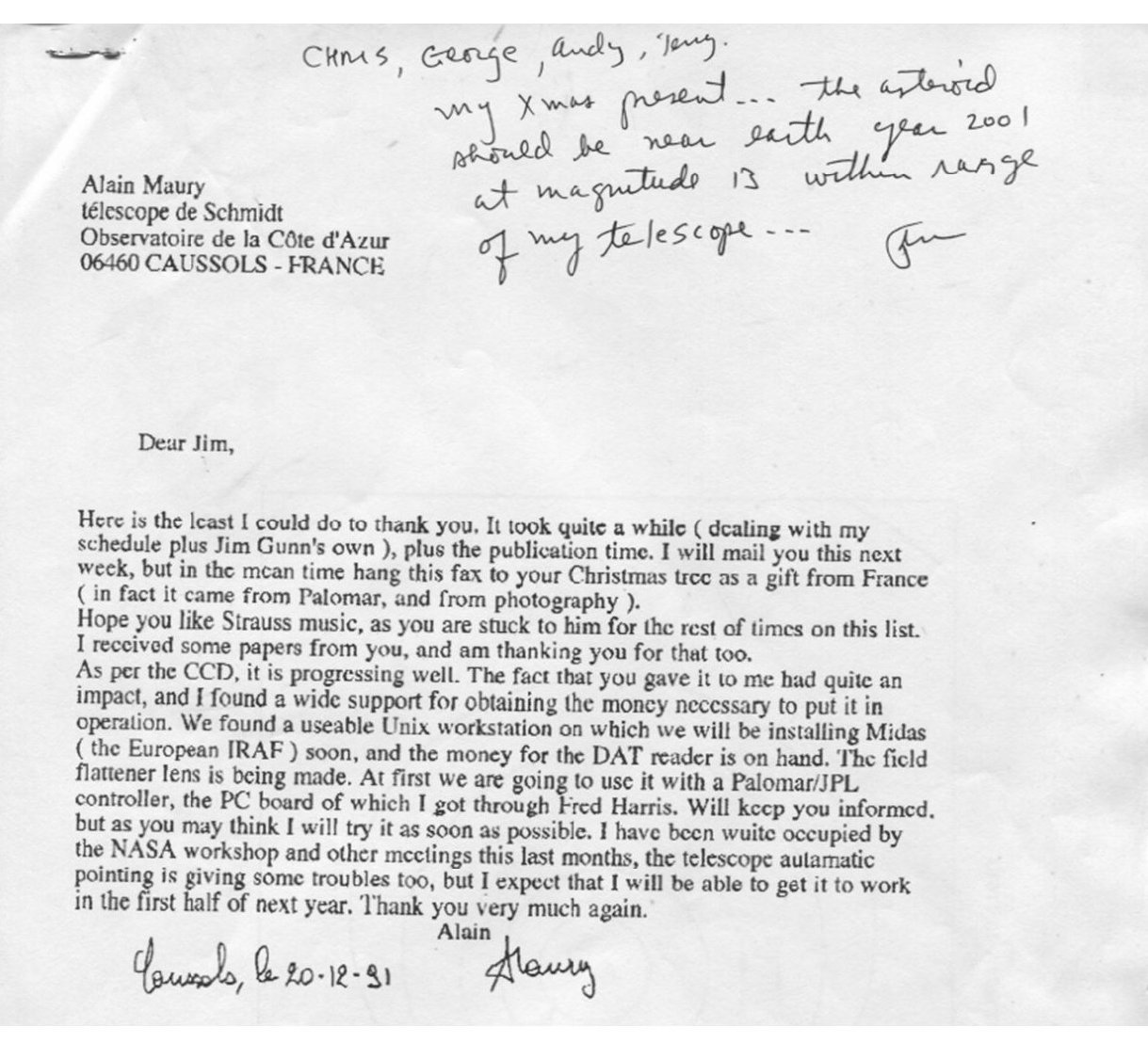

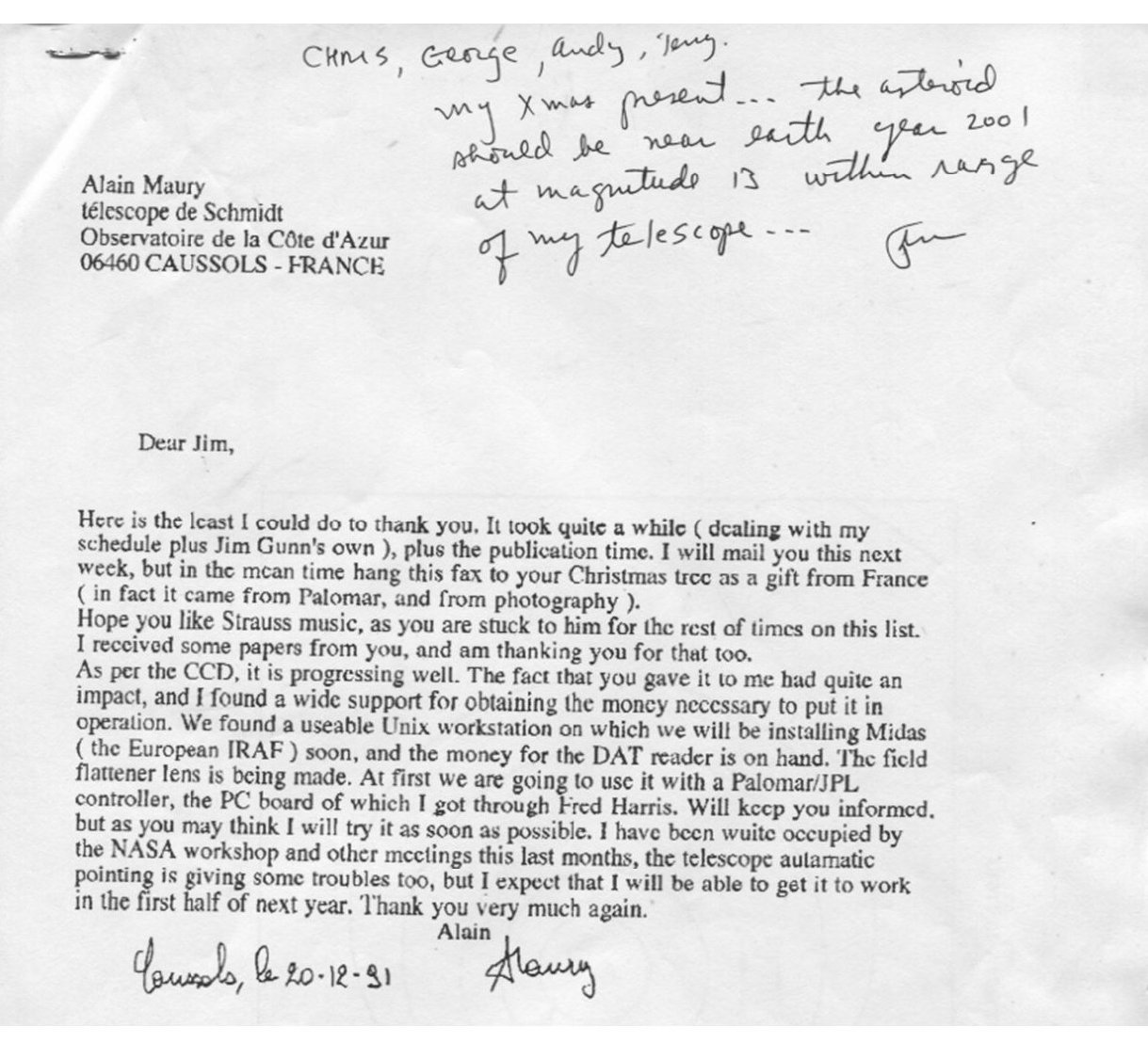

Letter by Alain Maury, co-discover of asteroid 4558, informing Janesick that the asteroid had been named in his honor.

Patents by James R. Janesick:

Photosensor with Enhanced Quantum Efficiency

Patent Number: 4,022,740

http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20080005928.pdf

Multipinned Phase Charge-Coupled Device

Patent Number US 4963952 A

http://www.google.com/patents/US4963952

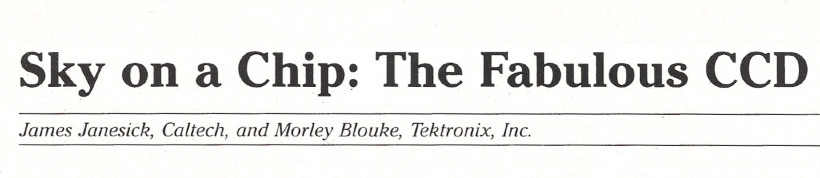

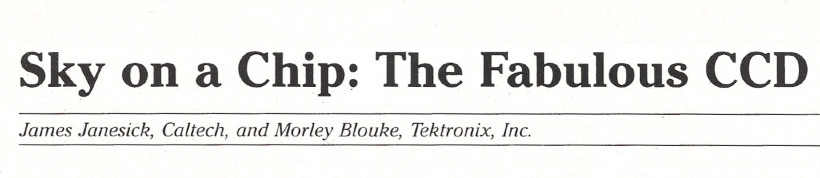

First Sky & Telescope Article on astronomical CCDs - 1987. Read the first ever article in Sky and Telescope concerning astronomical use of CCDs by clicking on the URL below.

http://www.phy.duke.edu/~kolena/sky_on_a_chip.pdf

Below is a very brief summary we have have made of Chapter 1.1

from Janesick's 2001 book, Scientific Charge-Coupled Devices, outlining

the early history of scientific CCDs.

Scientific Charge-Coupled Devices

Chapter 1.1, Scientific CCD History

James R. Janesick

The charge-coupled device (CCD) was invented 19

October 1969 by WillardS. Boyle and George E. Smith at Bell Telephone

Laboratories. Several weeks after developing the idea they

produced a simple working model and were able to successfully

demonstrate the validity of their idea. Although the CCD was

originally intended to be a memory device, its possible usefulness as

an imaging detector soon became apparent. CCDs had a number of

theoretical advantages over film and image tubes such as being able to

stare at objects for extended periods of time if properly cooled,

extreme sensitivity to visible light and near infra red (up to 100

times more so than film), excellent linear response (film has an

s-shaped response to light showing little effect at first, then a

period of linear response, then a drop off in response, then a reversal

effect whereby added light makes a white spot on a negative rather than

a darker black spot). In addition, a CCD has a very broad dynamic

range (can produce useful images of subjects with a very wide range of

light intensity from very bright areas to very dark areas). CCDs

are geometrically stable, small in size, very rugged, consume very

little power, and the images generated can easily be amplified

and digitized. All of these characteristics combined made the

newly developed CCD the imager of choice for the proposed Hubble

Telescope (originally called the LST, Large Space Telescope).

The first commercially available CCD demonstrating

its potential was a 100 x 100 pixel CCD manufactured by

Fairchild. It was used to produce the first known astronomical

CCD image, a photo of moon craters taken by James Janesink using an

eight-inch telescope and a Heath Kit oscilloscope. Eventually, a

400 x 400 pixel CCD was developed by Texas Instruments that performed

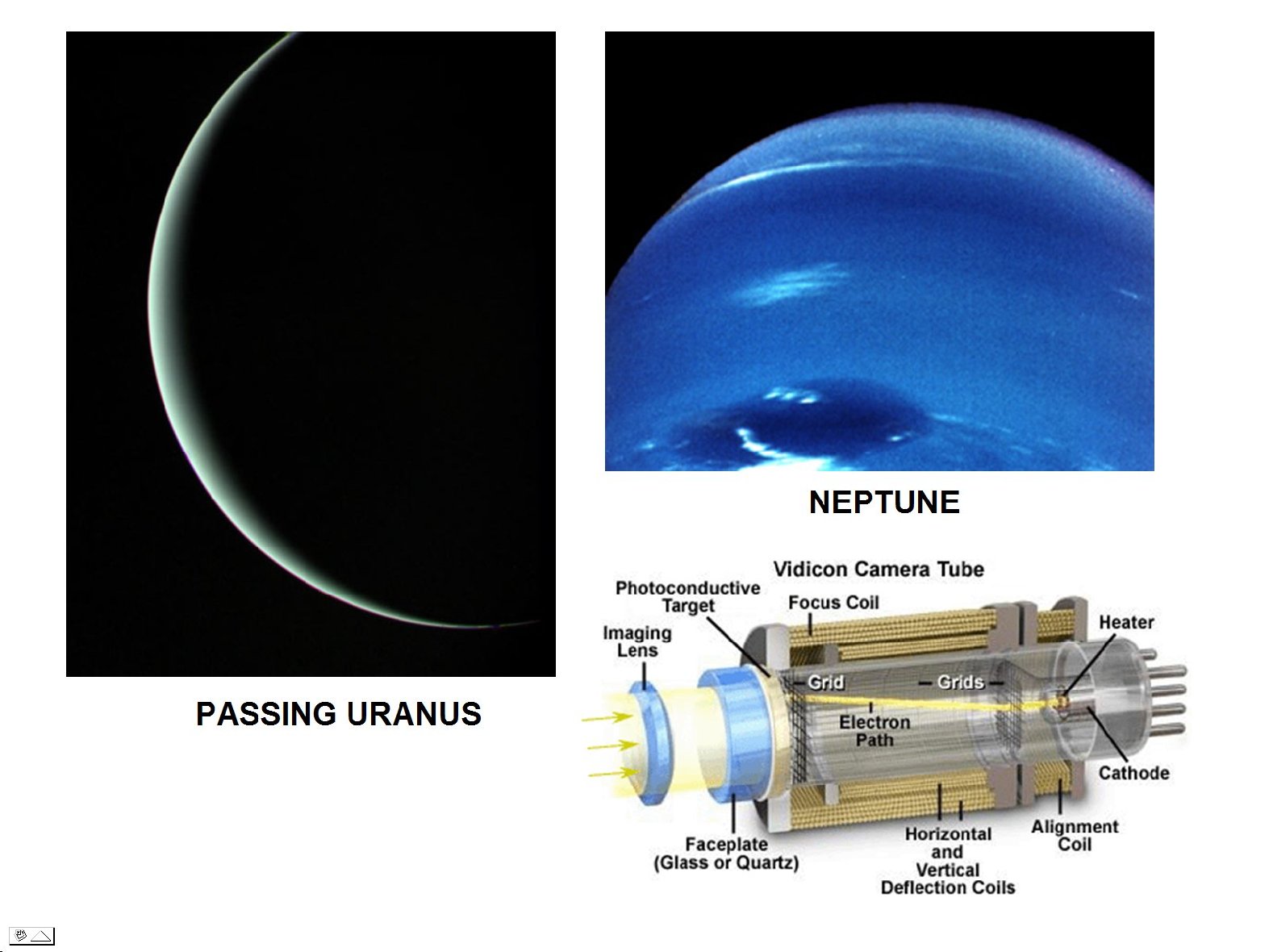

exceptionally well compared to vidicon tubes of that time. To

demonstrate to astronomers the many advantages of CCDs over film and

imaging tubes, JPL (Jet propulsion Lab) built a Traveling CCD Camera

System which resulted in new astronomical discoveries as it traveled

from one observatory to another - it was a huge success. As a

result, demand for CCDs by astronomers grew rapidly almost

overnight. Within a few years it became the imager of choice at

most observatories. With a light sensitivity 100 times greater

than film, CCDs made visible previously invisible stars and distant

galaxies.

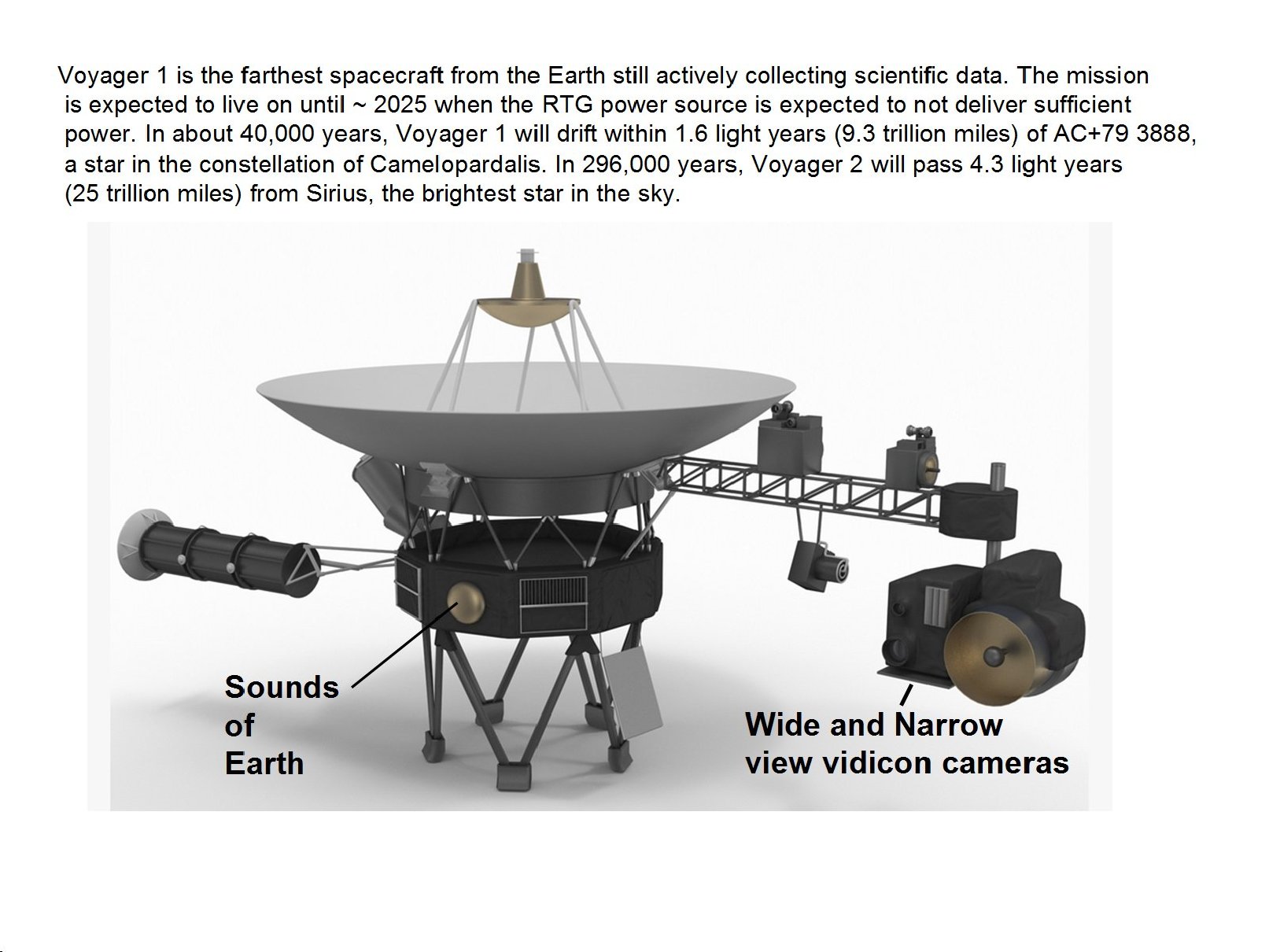

NASA reviewed several proposed imaging systems for

their then forthcoming Hubble Telescope and selected a JPL/Caltech

design that consisted entirely of CCD imagers. It was called the

Wide Field/Planetary Camera (WP/FC) Instrument. The first Hubble

telescope WP/FC used eight Texas Instruments 800 x 800 pixel

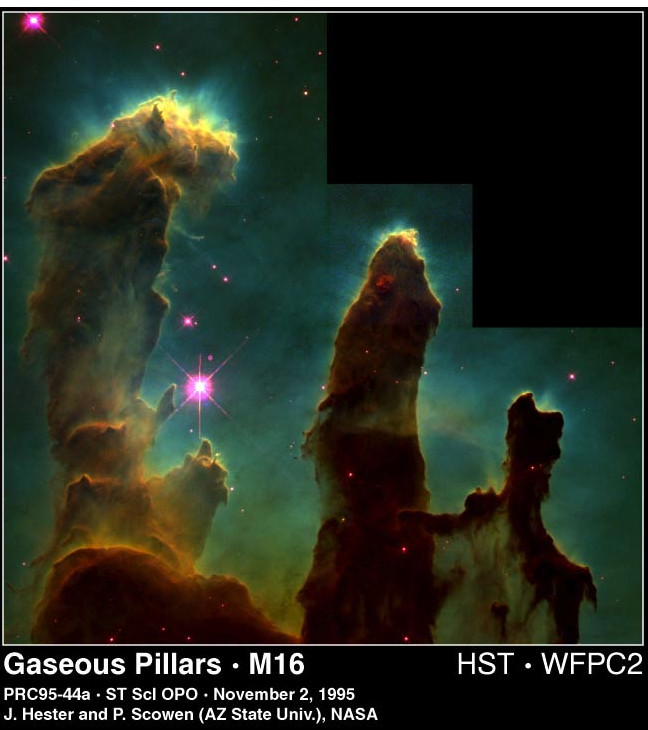

CCDs. Later, a second generation WP/FC with corrected lenses was

fitted with four Lockheed 800 x 800 pixel CCDs. With these

cameras the Hubble Telescope has been able to produce images all the

way to the visible horizon of the universe (see Deep Field

photo below).

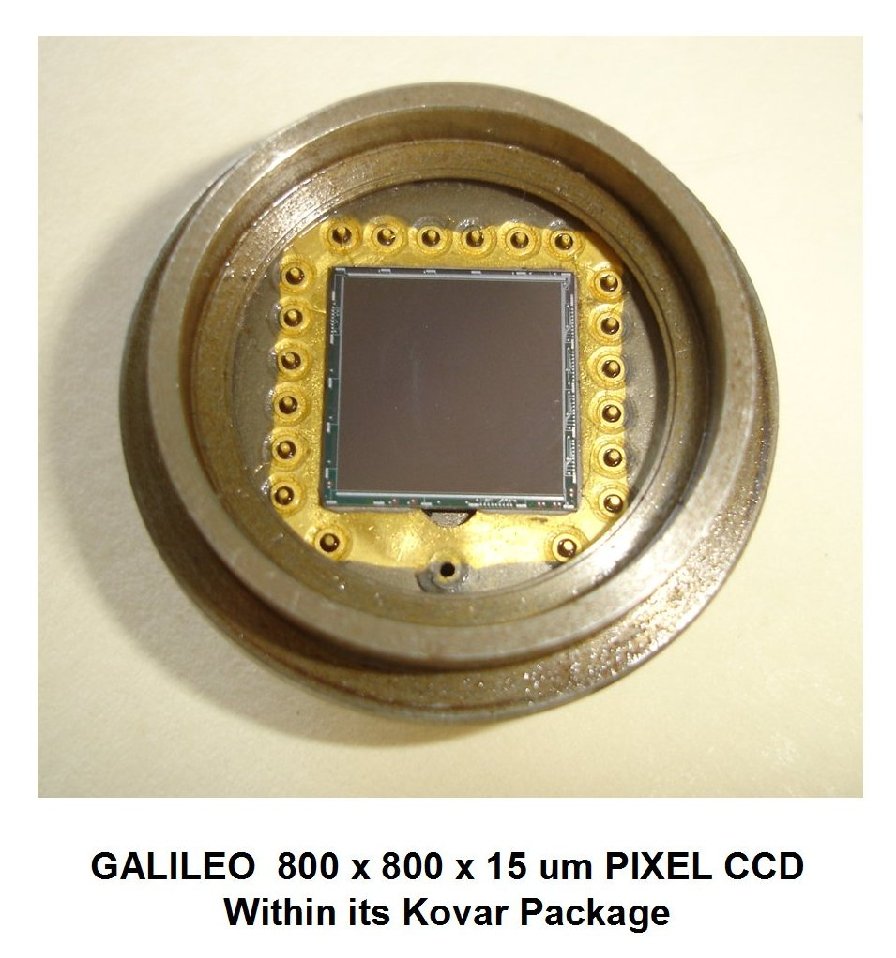

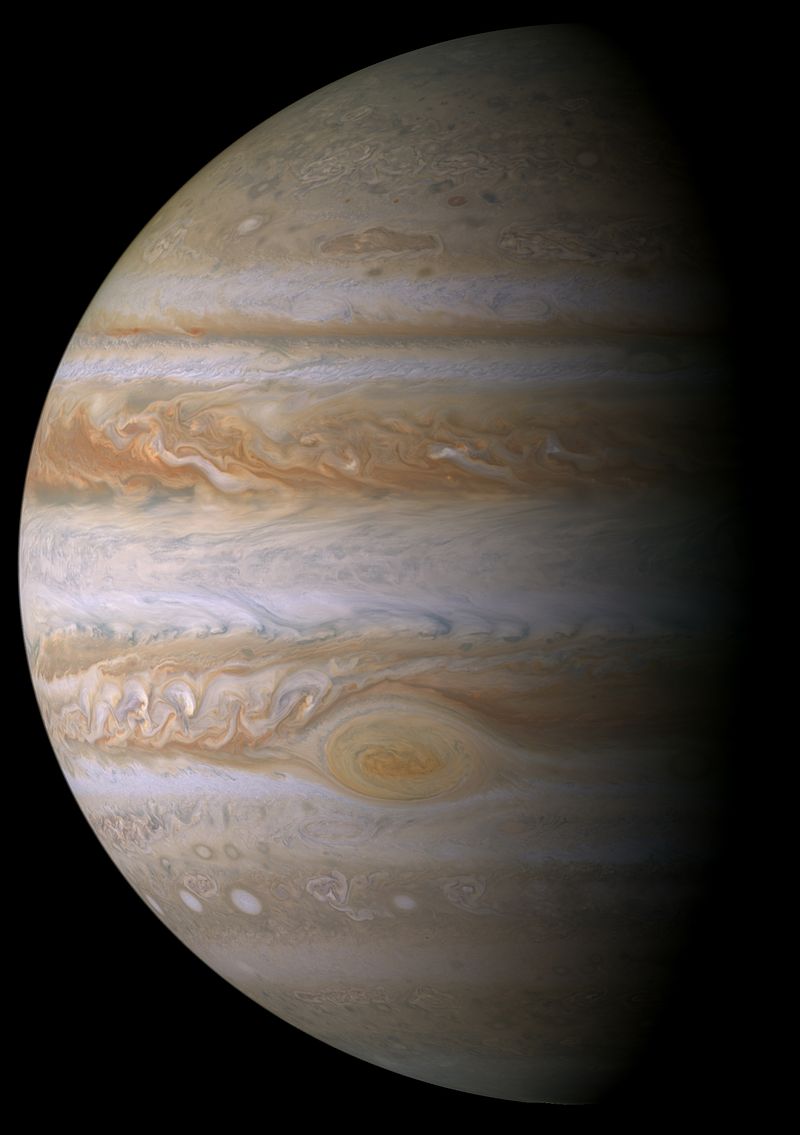

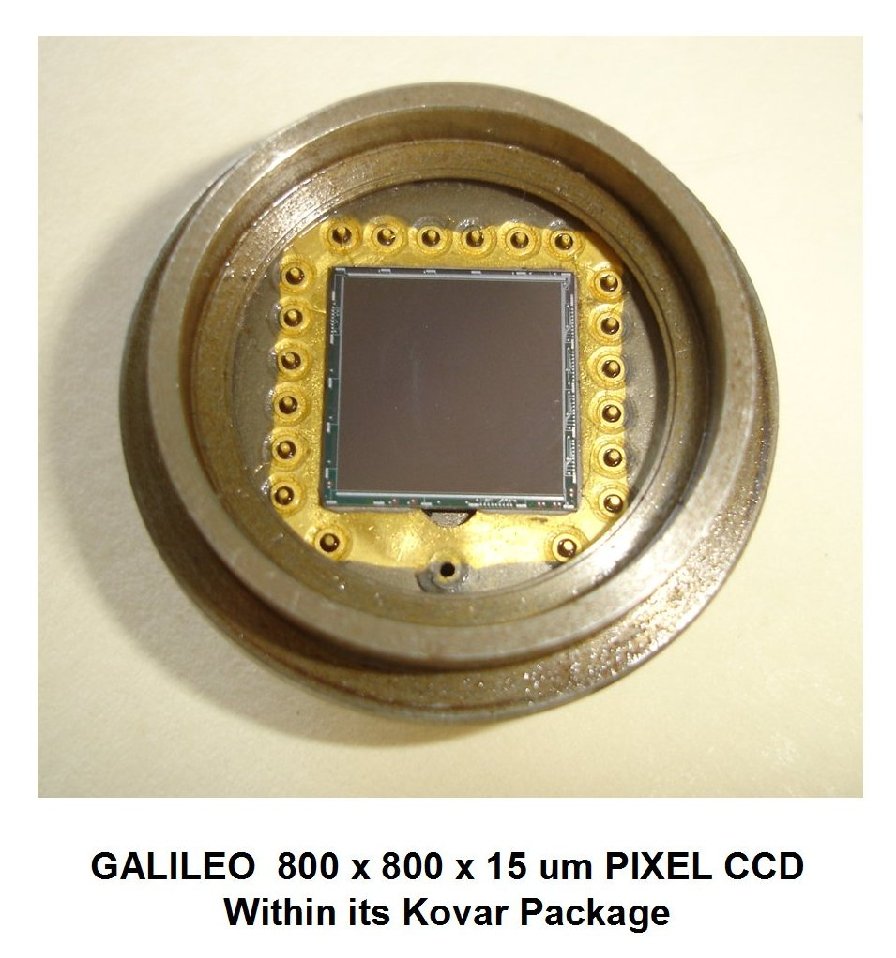

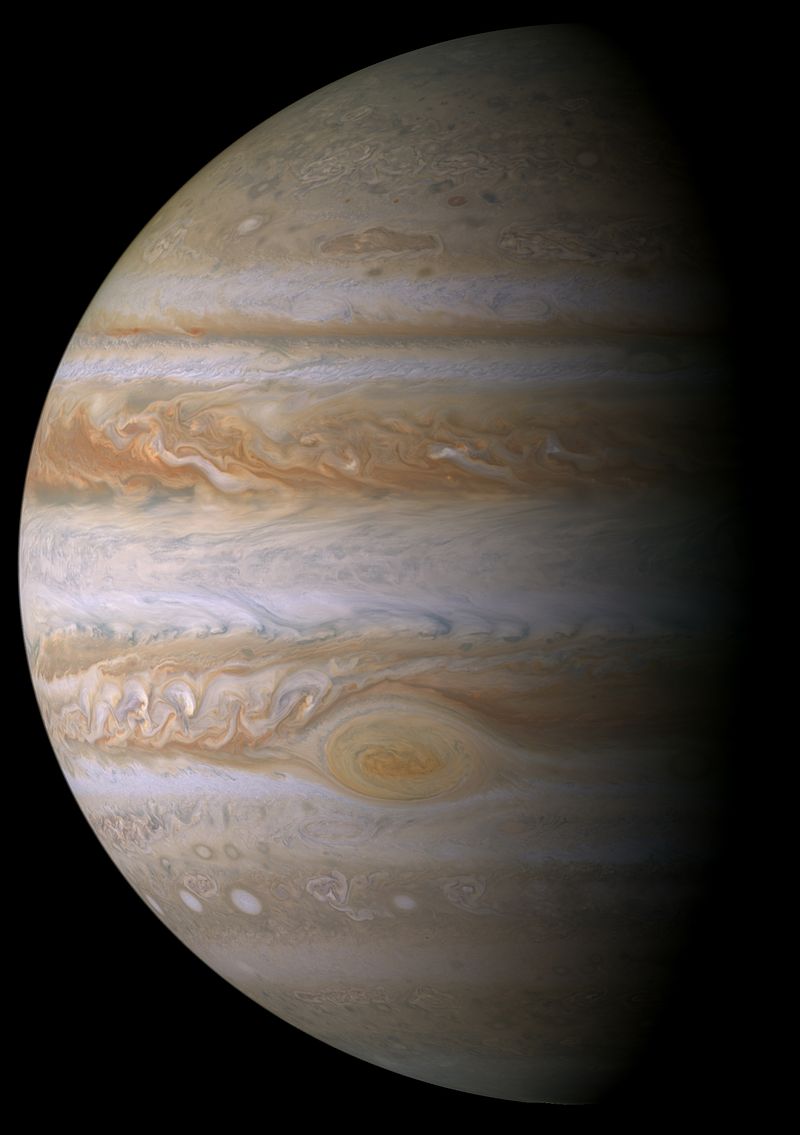

On 18 October 1989 the spacecraft Galileo was

launched to study Jupiter and its moons. It consisted of an

orbiter and an entry probe. Its Solid State Imaging (SSI) camera

used a Texas Instruments 800 x 800 pixel CCD. On the way to

Jupiter it took a photo of asteroid Ida (which is about 35 miles long)

and its newly discovered moon, Dactyl. Dactyl was the first ever

asteroid moon to be discovered and is only about one mile in diameter

(see photo below).

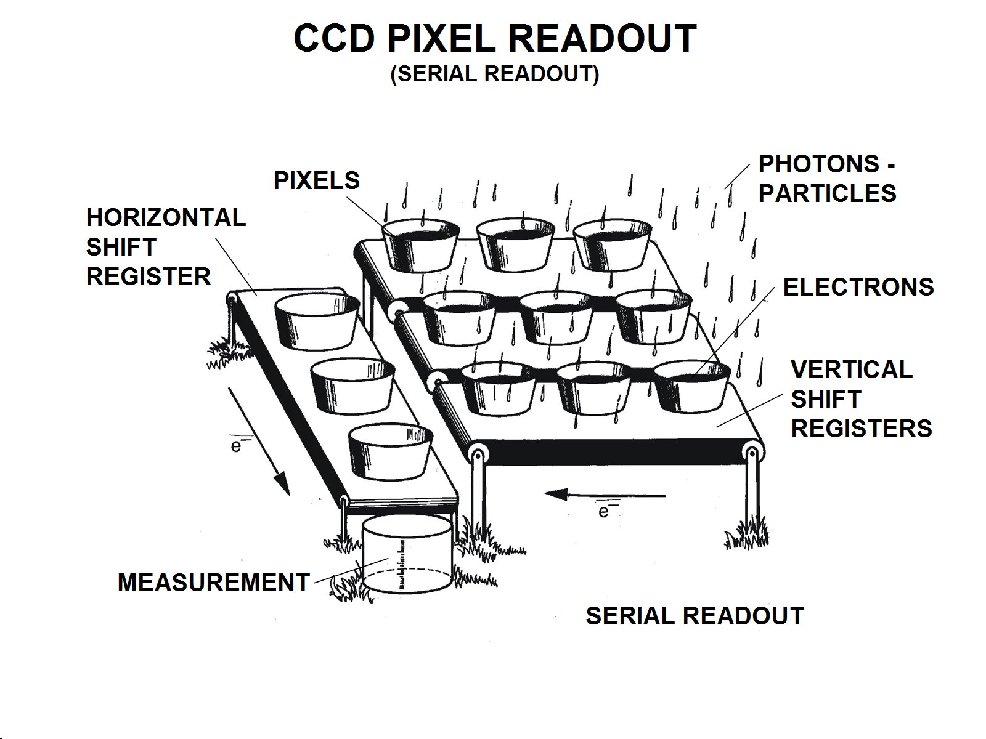

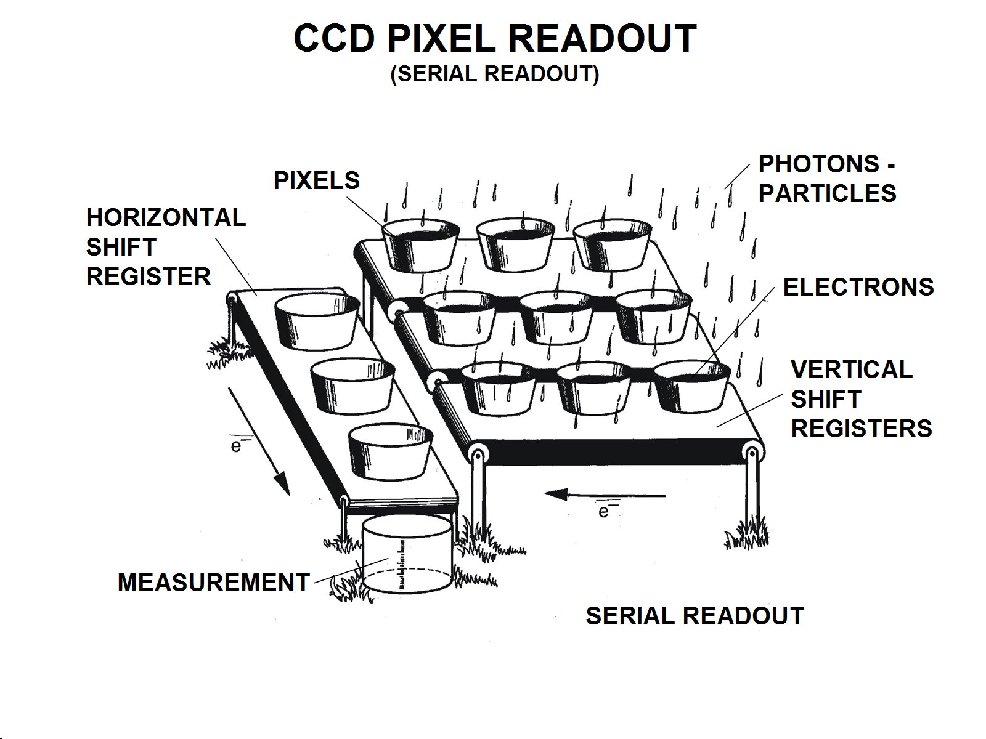

CCDs work electronically in a way similar to the

illustration below. If you wished to determine the efficiency of

a water sprinkler system you could place a number of bucket across the

sprinkler's watering area and then measure the amount of water in each

bucket to see whether they were filled fairly uniformly. In the

below illustration an automatic system is envisioned whereby the filled

buckets are transported by conveyer belts and dumped into other buckets

on a belt which runs perpendicular to the first belts. They are

then transported to a measuring system. Imagers in your camera

work in a similar way such that the intensity of light striking each

pixel is accurately determined by measuring the charges created by

photons striking the camera imager. Every CCD imager has four

primary functions: 1) charge generation, 2) charge collection, 3)

charge transfer and 4) charge measurement. When the imager

in your camera performs these functions properly you get the beautiful

photos that have caused chemical photography to so rapidly become

obsolete.

HOW CCDS SHIFT CHARGES.

Historic CCDs and CCD Photos

(Below CCD photos provided to DigiCamHistory.Com by James R. Janesick)

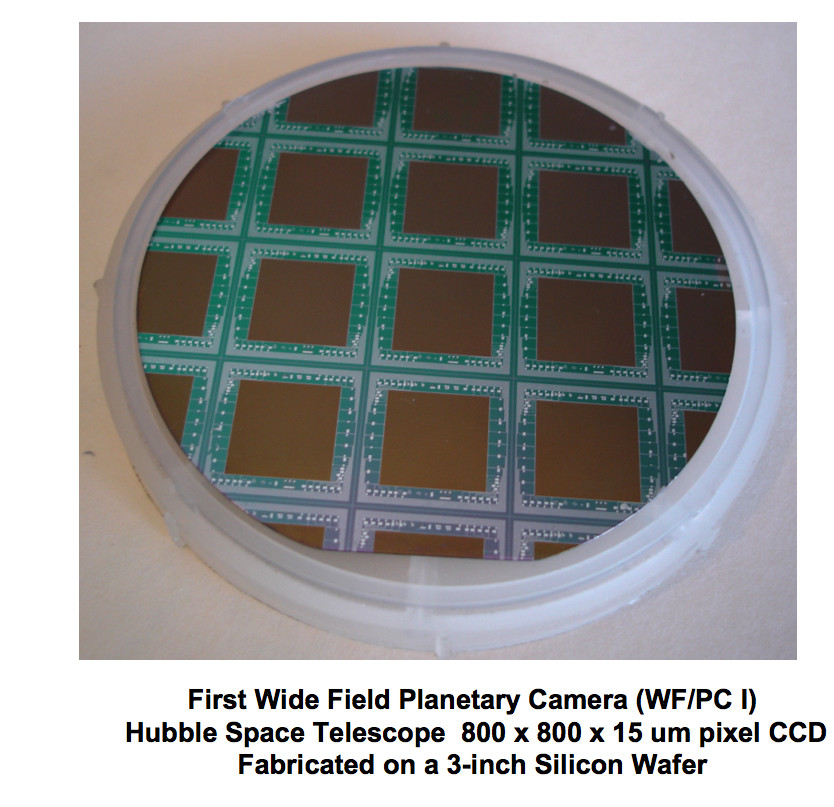

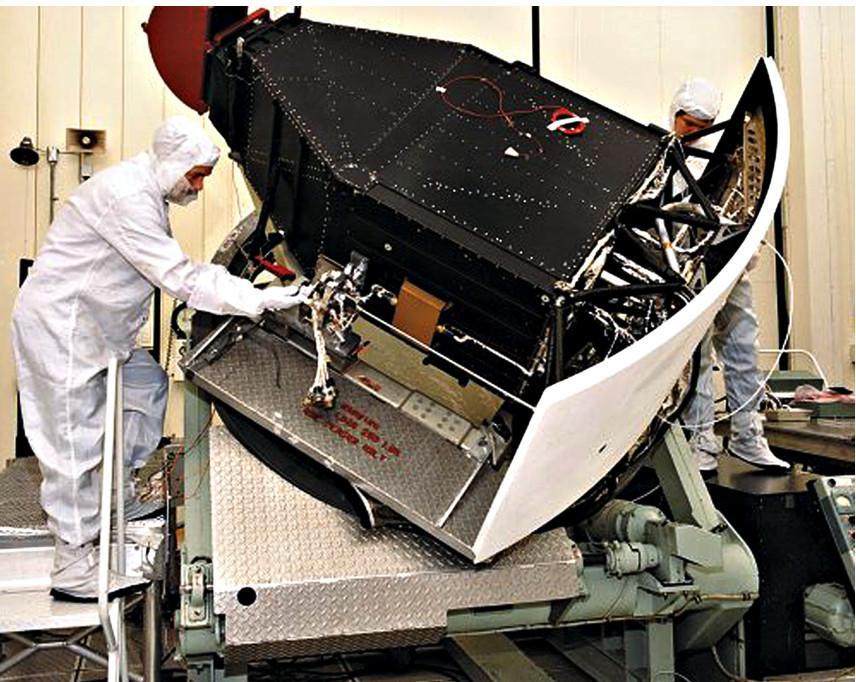

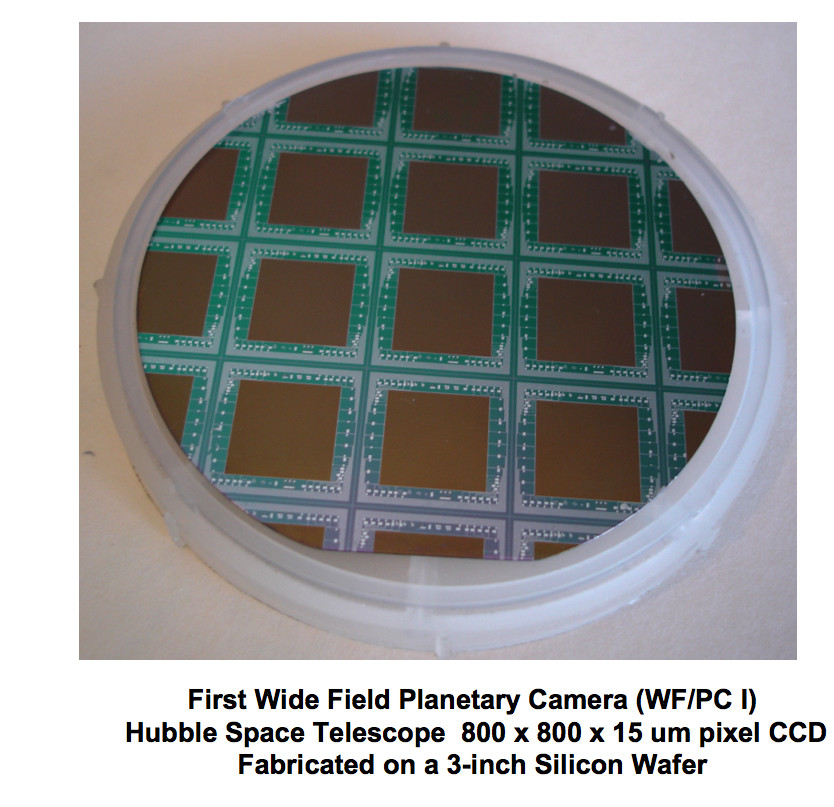

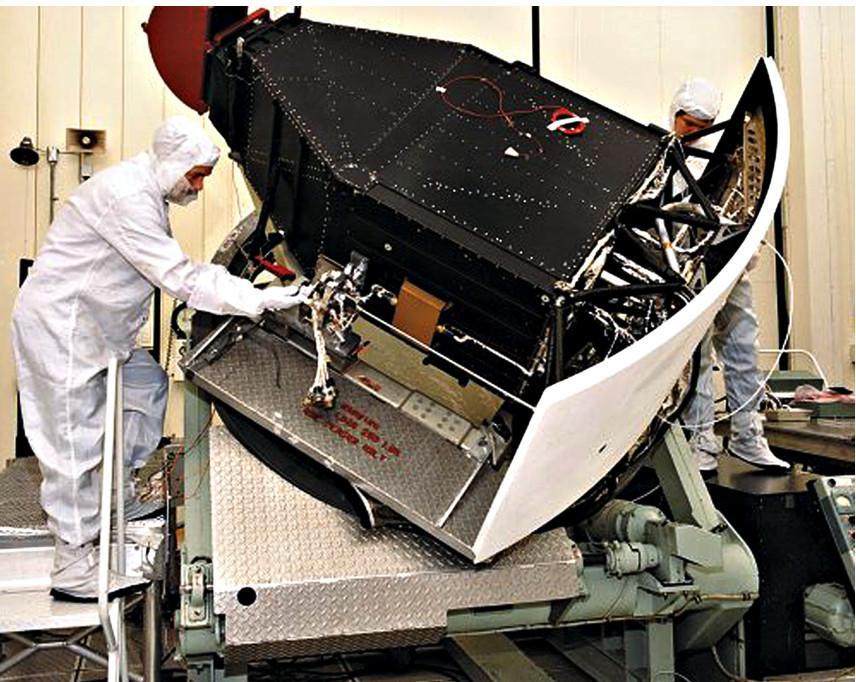

Hubble CCD wafer and Hubble in space.

WF/PC I used eight 800 x 800 x 15 um pixel CCDs. Four narrow

fields and three wilde fields are shown above with associated analog

electronics

(the missing wild field has not been installed yet). On its return to

Earth, the WFPC was disassembled and parts of it were used in Wide

Field Camera 3

which was installed in Hubble on May 14, 2009 as part of

Servicing Mission 4, replacing WFPC2. Photo on the right is the

camera system in its enclosure.

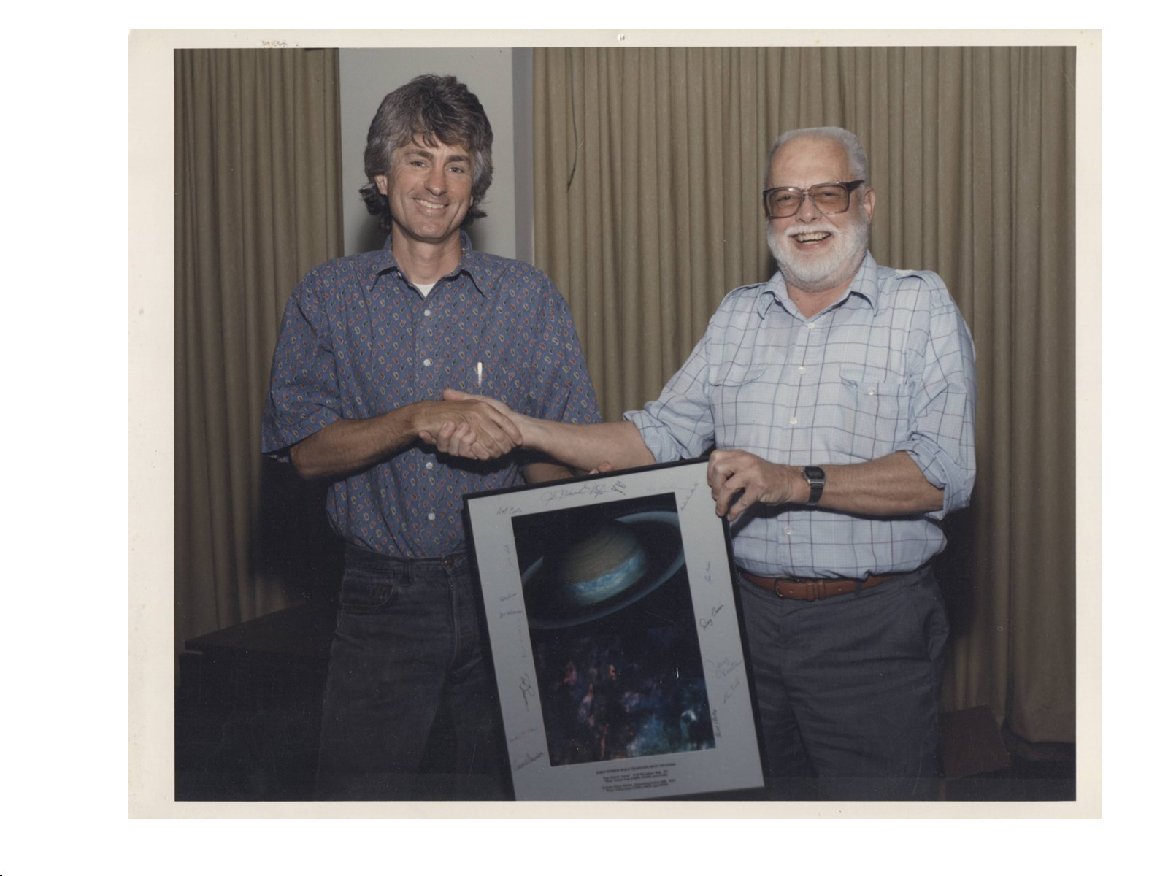

See 1990 page for more Hubble Telescope information. Photo on the left provided by James Janesick.

Photo is of Jim Janesick and Jim Westphal celebrating the success of the WF/PC camera used on the Hiubble Telescope.

(also see McCord / Westphal 1971 Digital Astronomy Project higher up on the 1970s page).

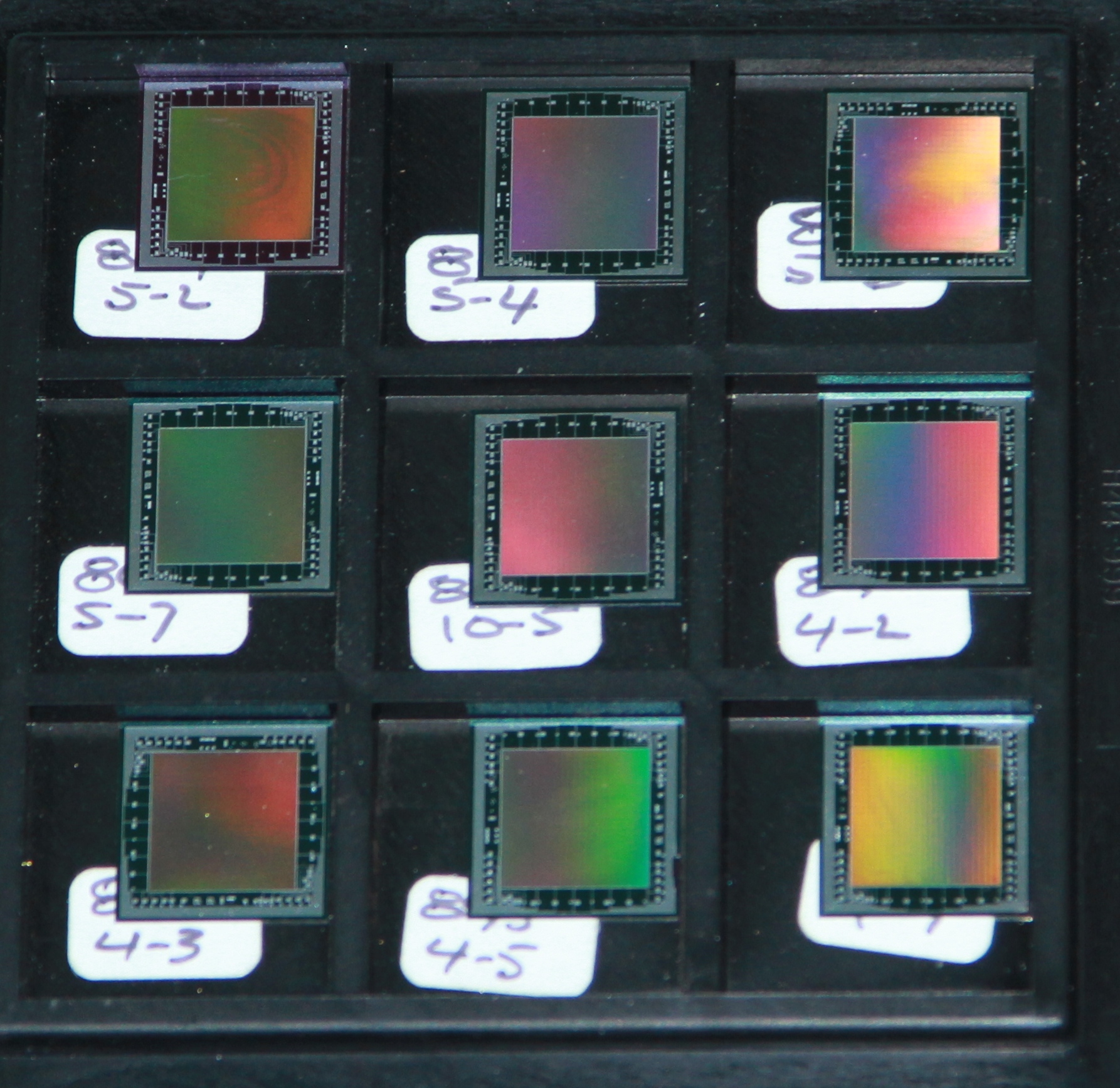

Left photo above is a group

of spare CCDs made for the Hubble

Wide Field/Planetary Camera (WF/PC) Instrument program and donated to DigiCamHistory.Com by James

Janesick. Each is about 1/2-inch square and 800 x 800 pixels (.64 MP). The

photo on the right was taken by Hubble of a small sliver

of space that appeared to be entirely empty whenviewed on film.

Due to the much greater sensitivity of CCDs versus film, more than ten

thousand previously unseen, unknown galaxies appeared. The total

number of visible galaxies now exceeds 200 billion.

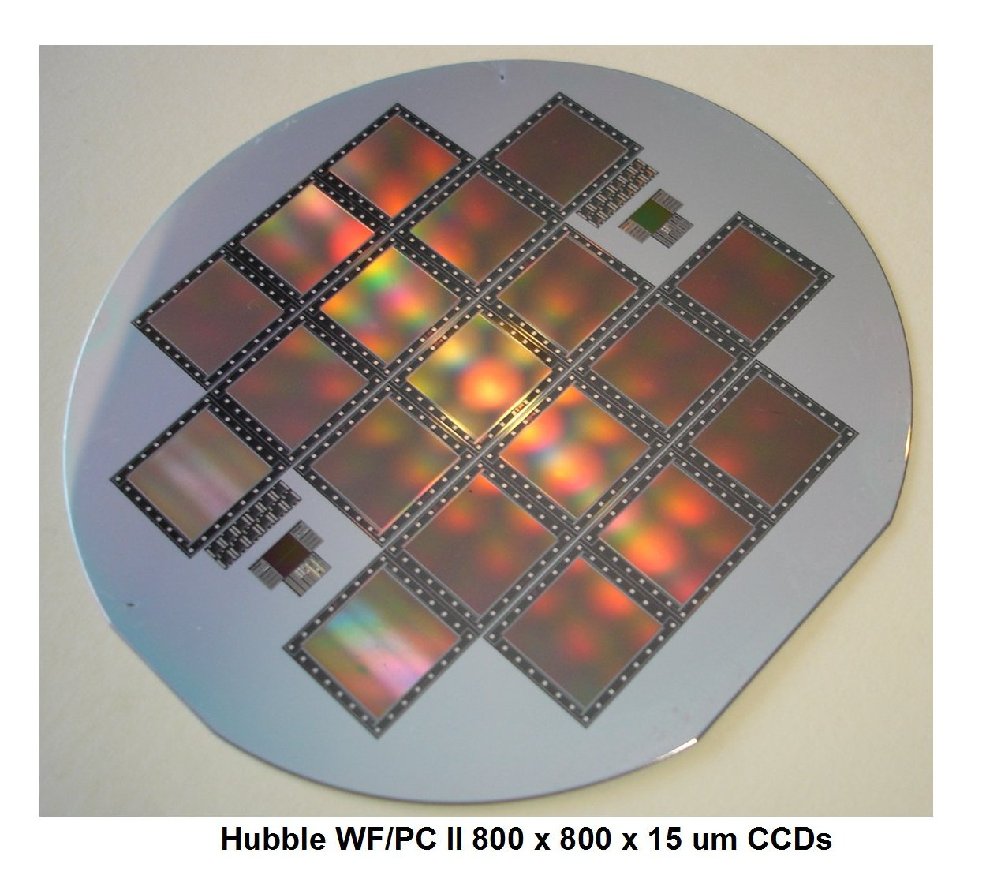

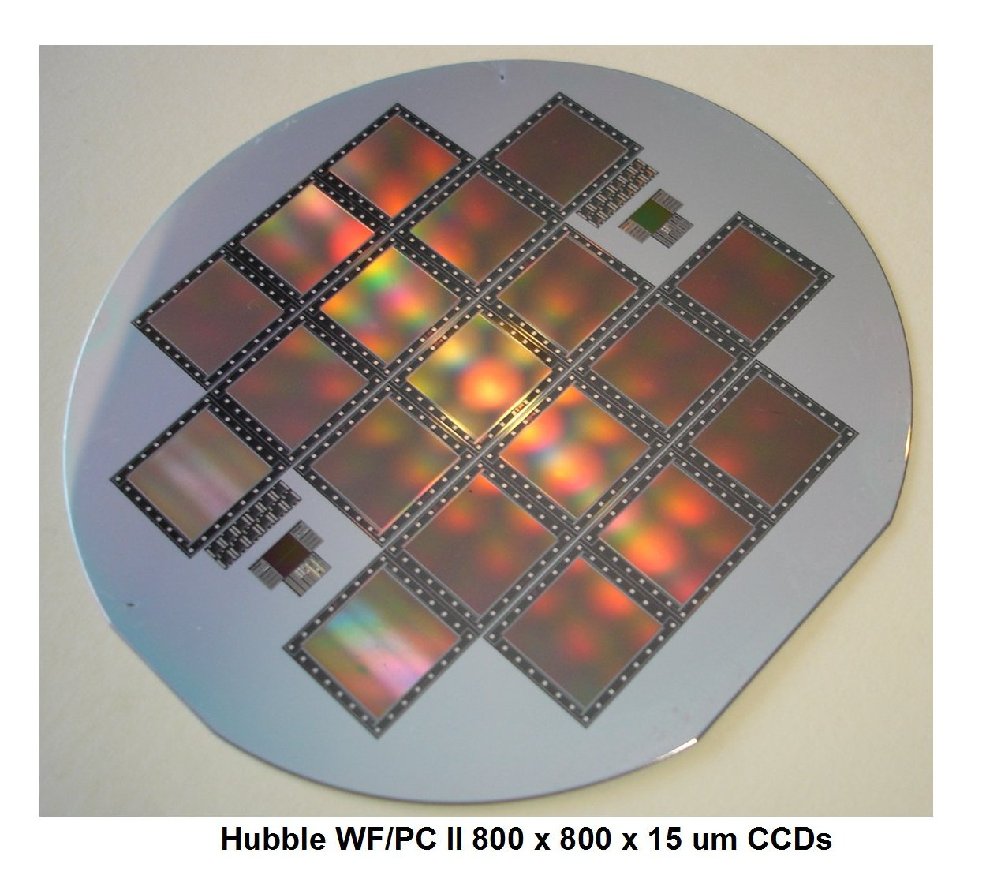

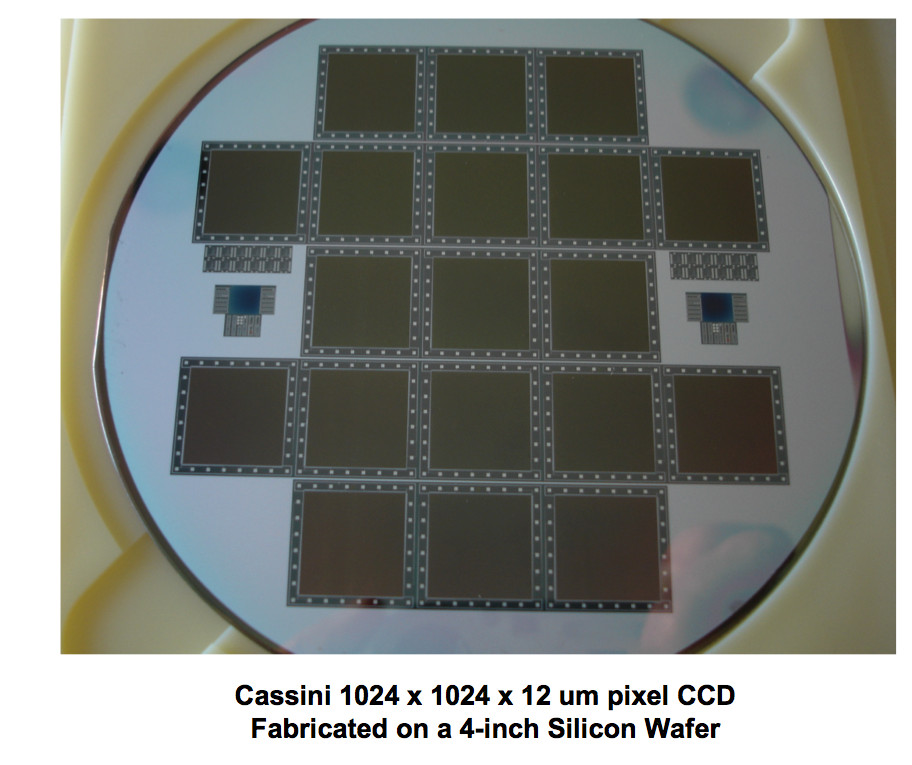

This silicon wafer contains the Hubble WF/PC II 800 x 800 x 15 um

imagers. Hubble's focus problem was fixed with the WF/PC II

camera. There were only 4 CCDs on this mission - 3

wide field (f/30) and 1 planetary(f12.0) instead of the eight used on

WF/PC I. WF/PC II was the most used instrument in the first 13

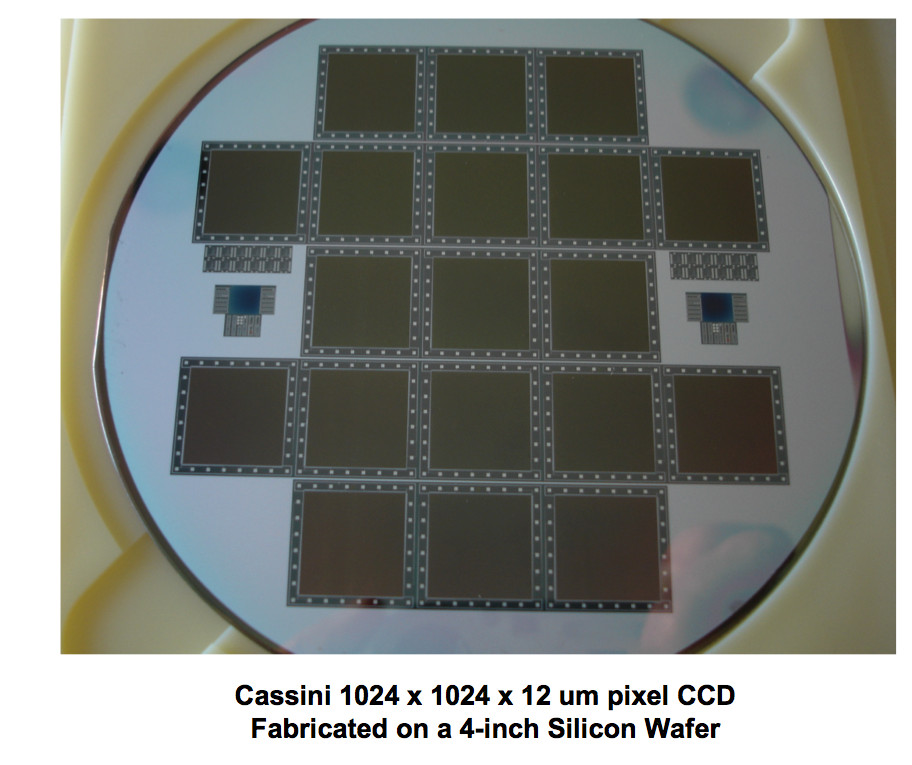

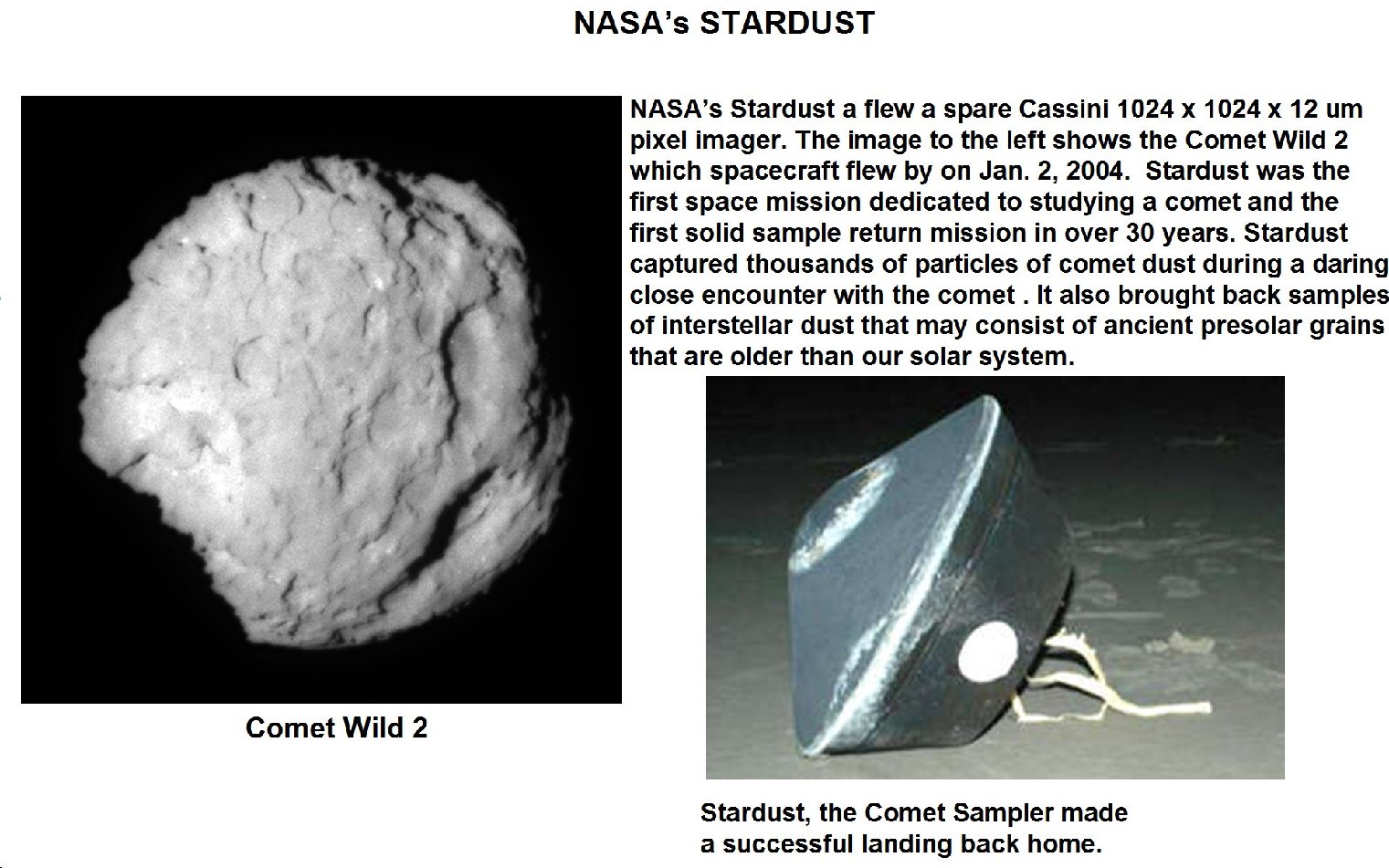

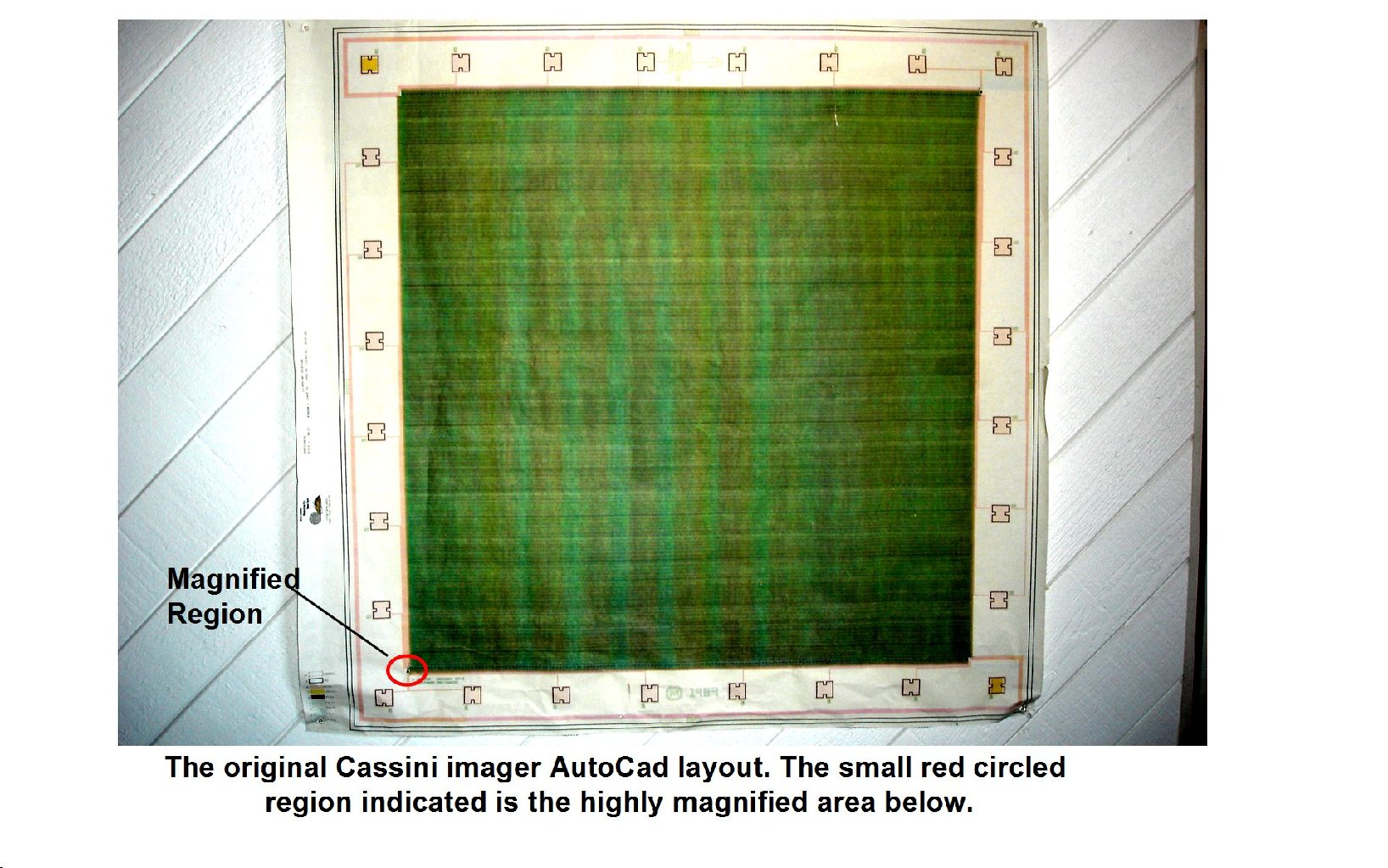

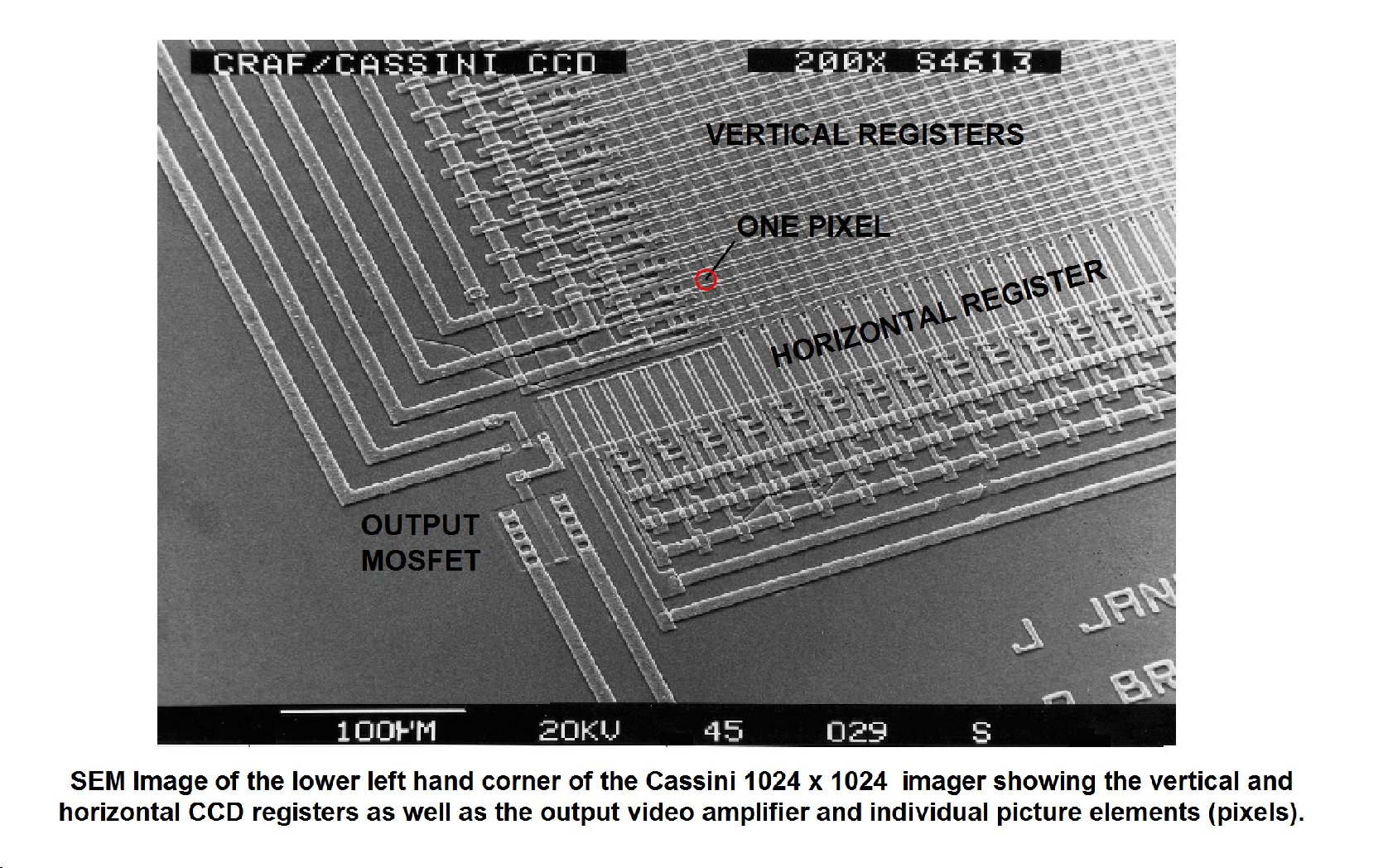

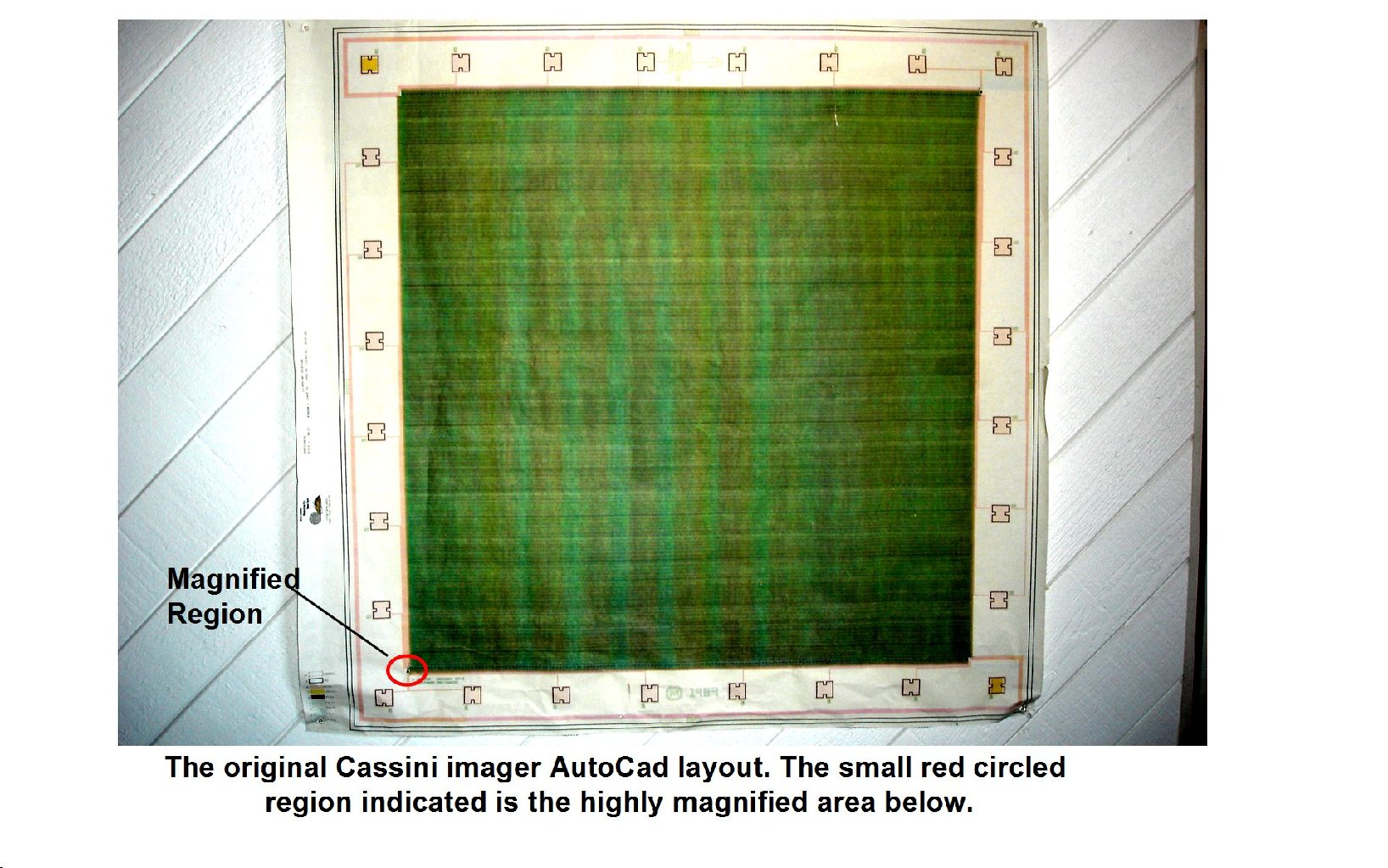

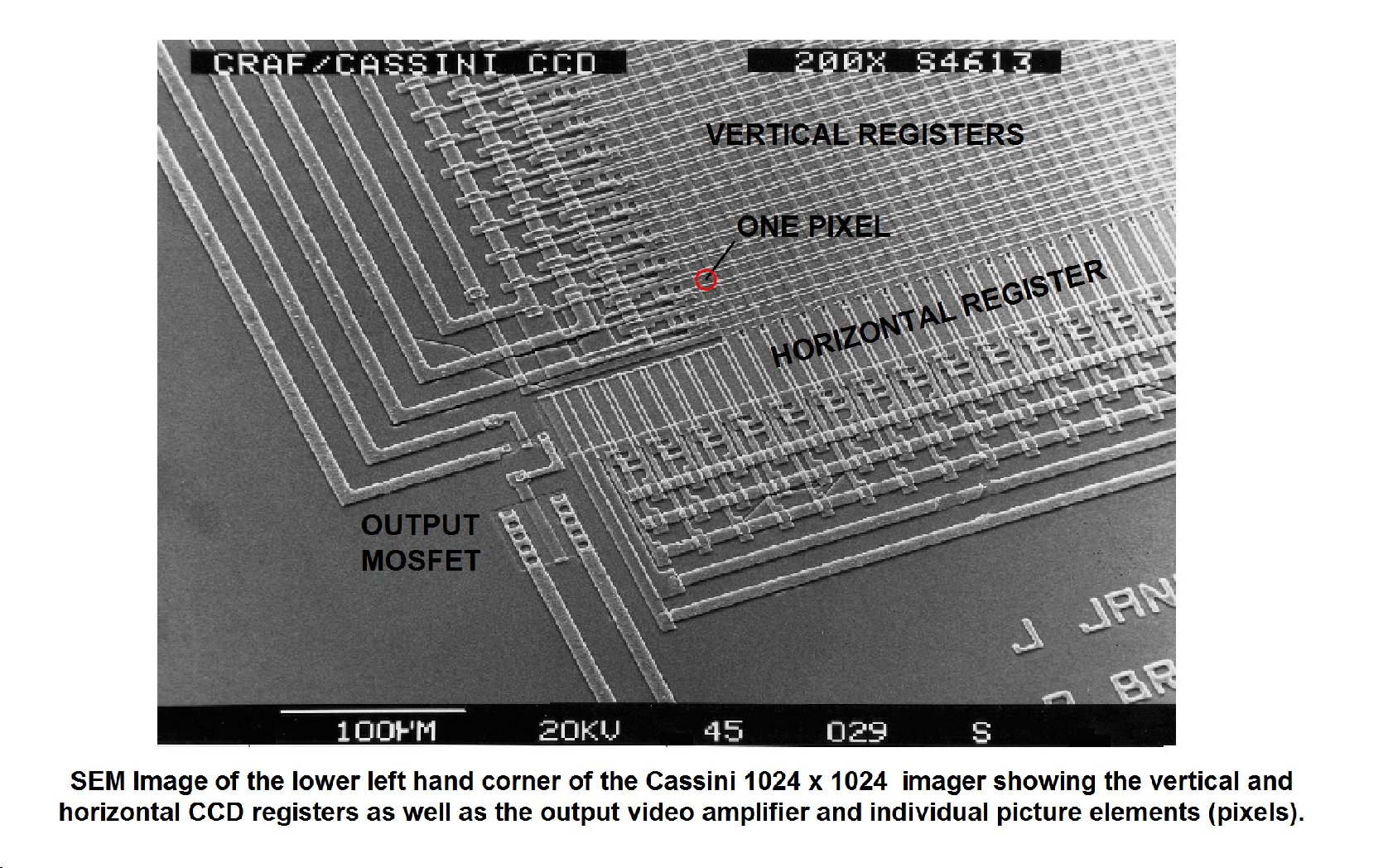

years of Hubble's life. The WF/PC II imagers and the Cassini 1024

x 1024 x 12 um imagers were fabricated at the same time (at Ford

Aerospace Newport Beach). Wafer photo by James Janesick.

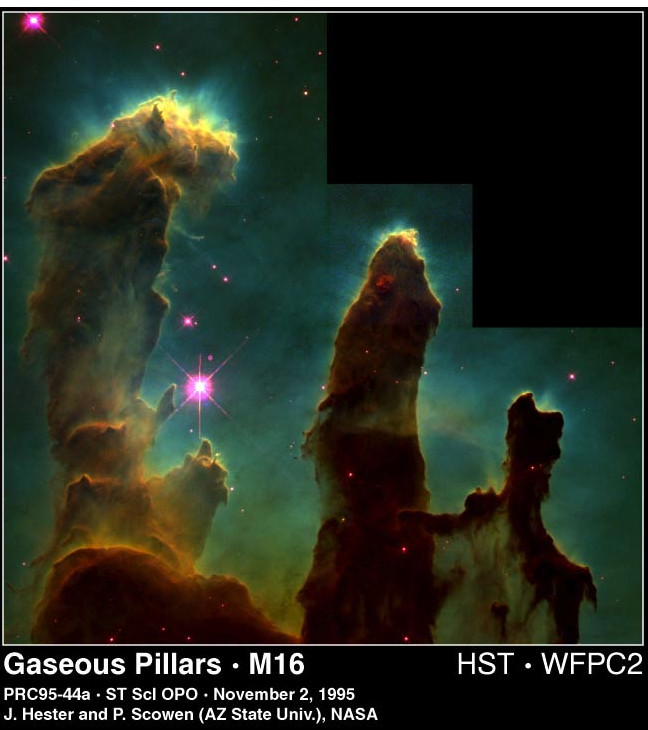

Photo on the right was by the corrected Hubble camera using WF/PC II.

The photo on the left is the spacecraft Galileo's CCD. On

the right is Galileo's camera that took the photo of Ida and its

moon.

Years of Jupiter's intense radiation took its toll on the spacecraft's

systems, and its fuel supply was running low in the early 2000s.

Galileo had not been sterilized, so to prevent contamination of

Jupiter's moons, a plan was formulated to send it directly into the

planet. Galileo was intentionally commanded to crash into

Jupiter, which eliminated the possibility it would impact Jupiter's

moons and seed them with bacteria. In order to crash into

Jupiter, Galileo flew by on November 5, 2002, during its 34th

orbit, allowing a measurement of the moon's mass as it passed within

101 mi of its surface. On April 14, 2003, Galileo reached its

greatest distance from Jupiter for the entire mission prior to orbital

insertion, 16,000,000 mi, before plunging back towards the gas giant

for its final impact. At the completion of its 35th and final

circuit around the Jovian system, Galileo impacted the gas giant in

darkness just south of the equator on September 21, 2003. Its impact

speed was approximately 107,955 mph.The total mission cost was about

US$1.4 billion. (James R. Janesick)

This image is

of the asteroid Ida and its small moon Dactyl in a photo taken by the

spacecraft Galileo, the first of an asteroid with its own moon.

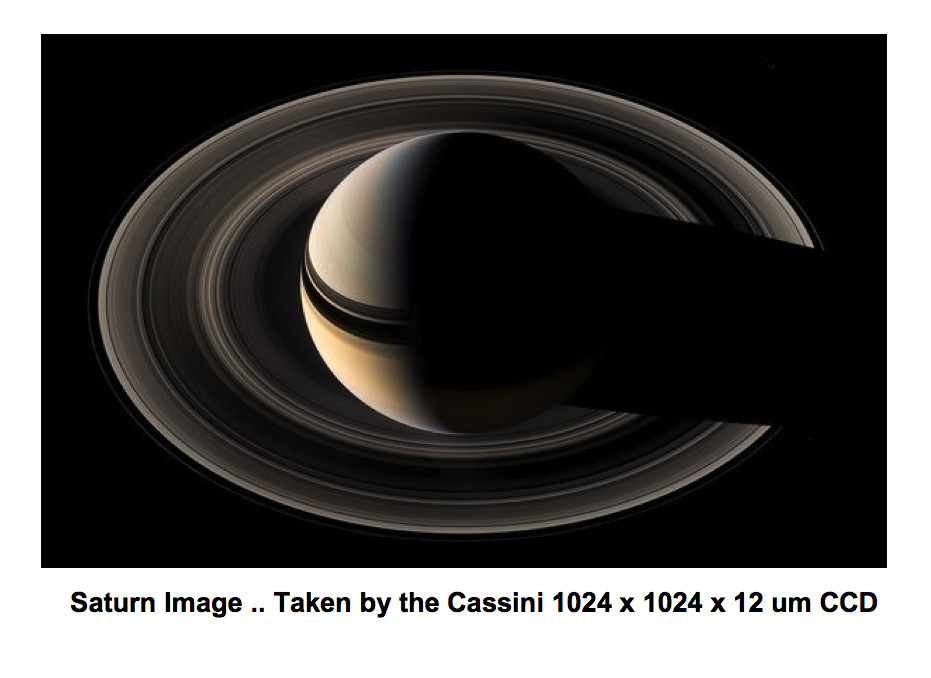

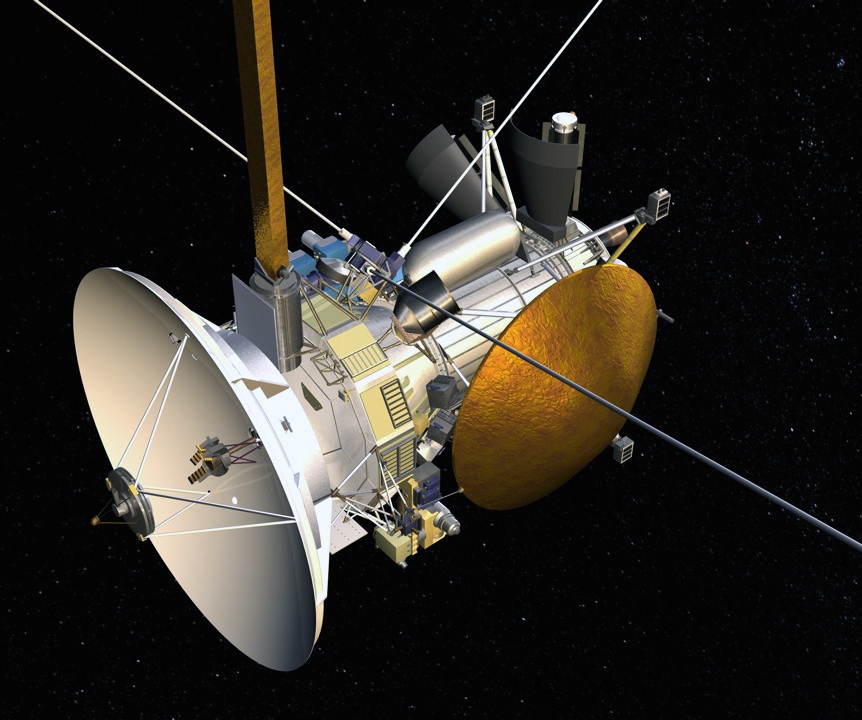

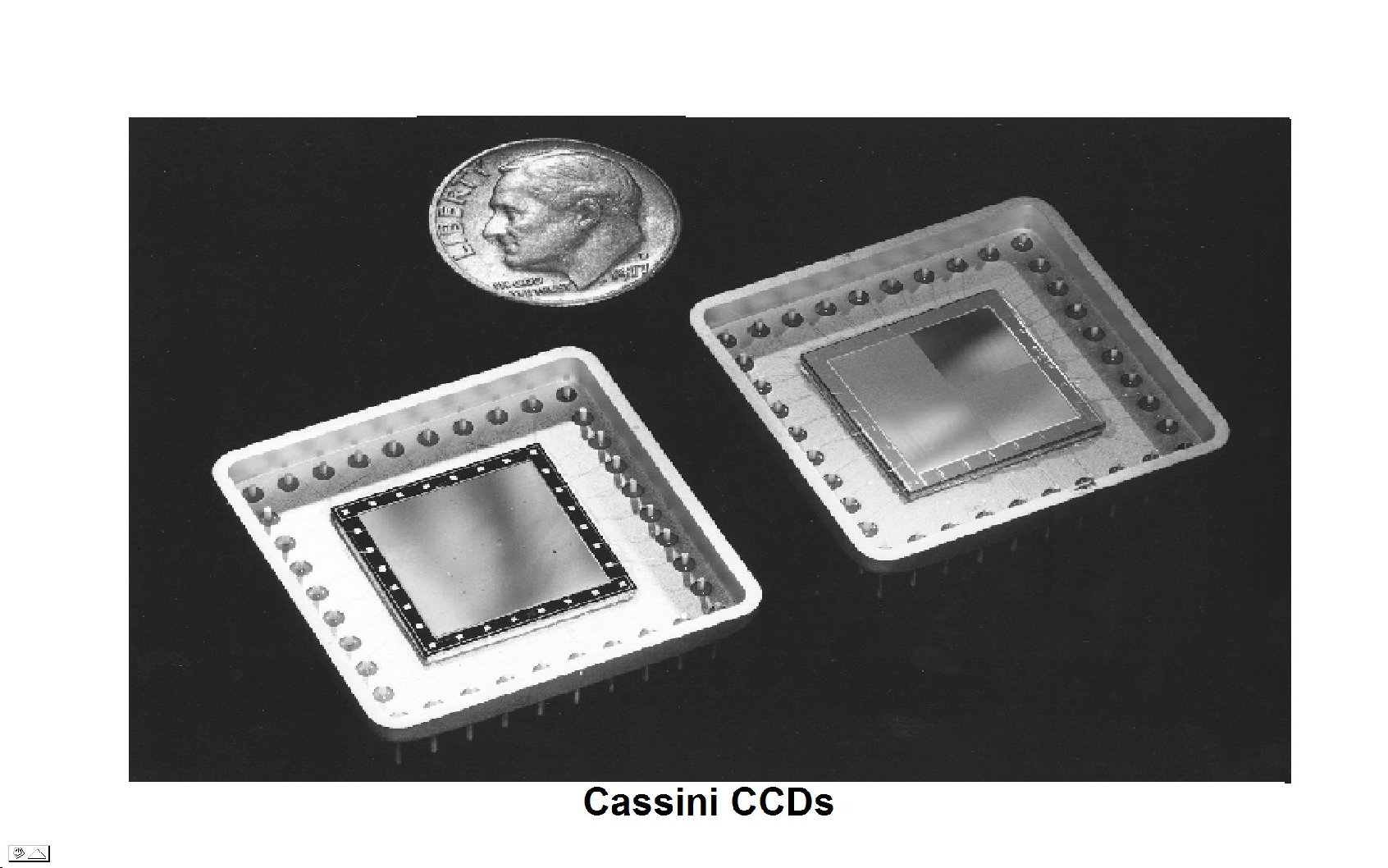

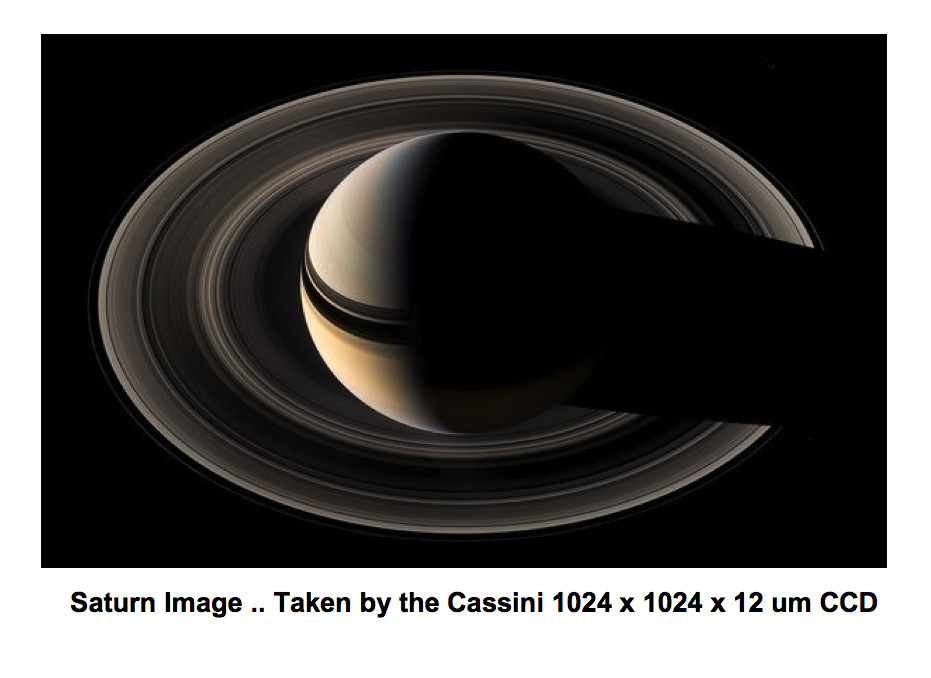

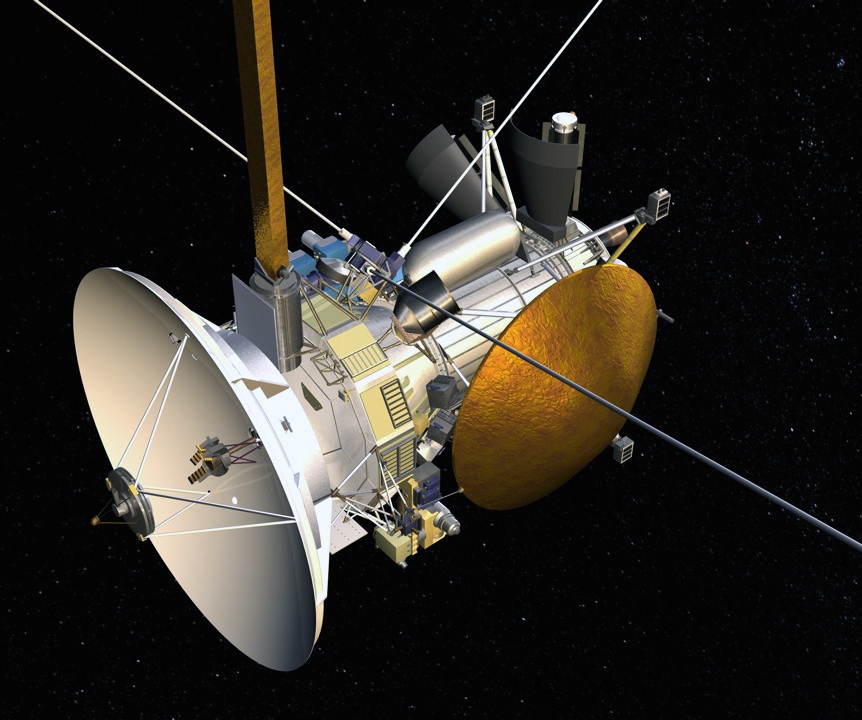

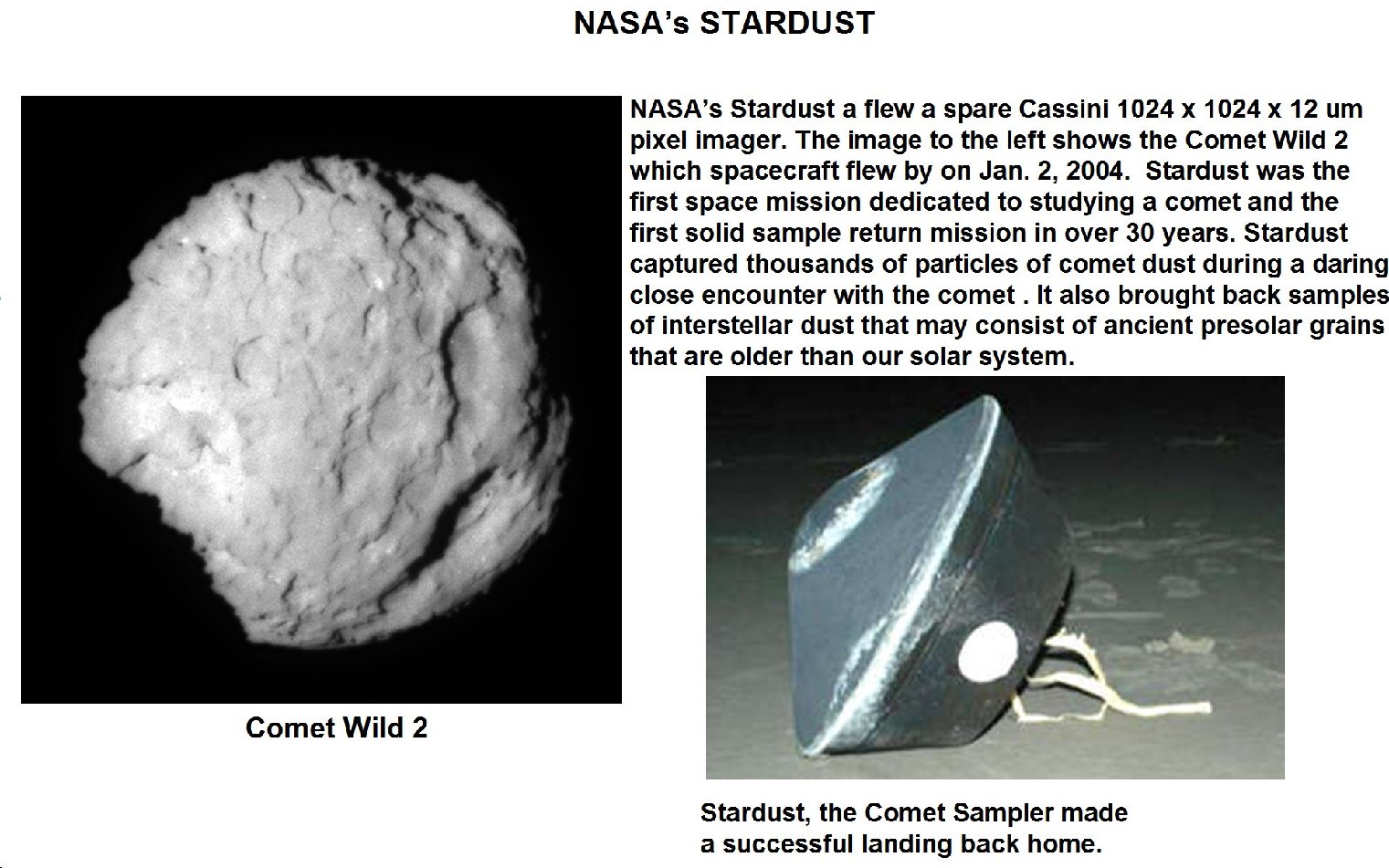

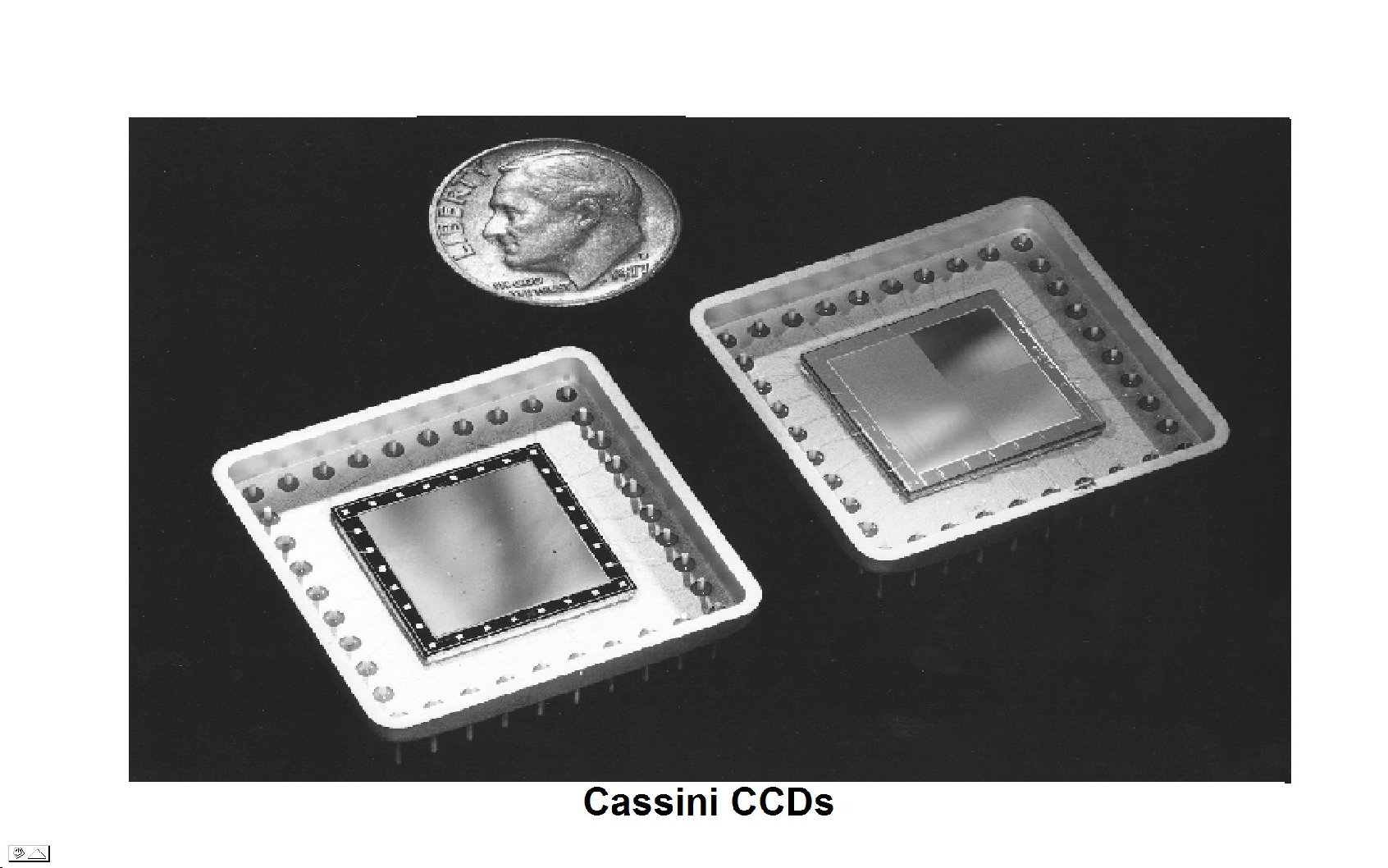

The photo on the left is the spacecraft Cassini's CCD. The photo

on the right is of Saturn taken by the spacecraft Cassini.

Spacecraft Cassini and image it took of Jupiter.

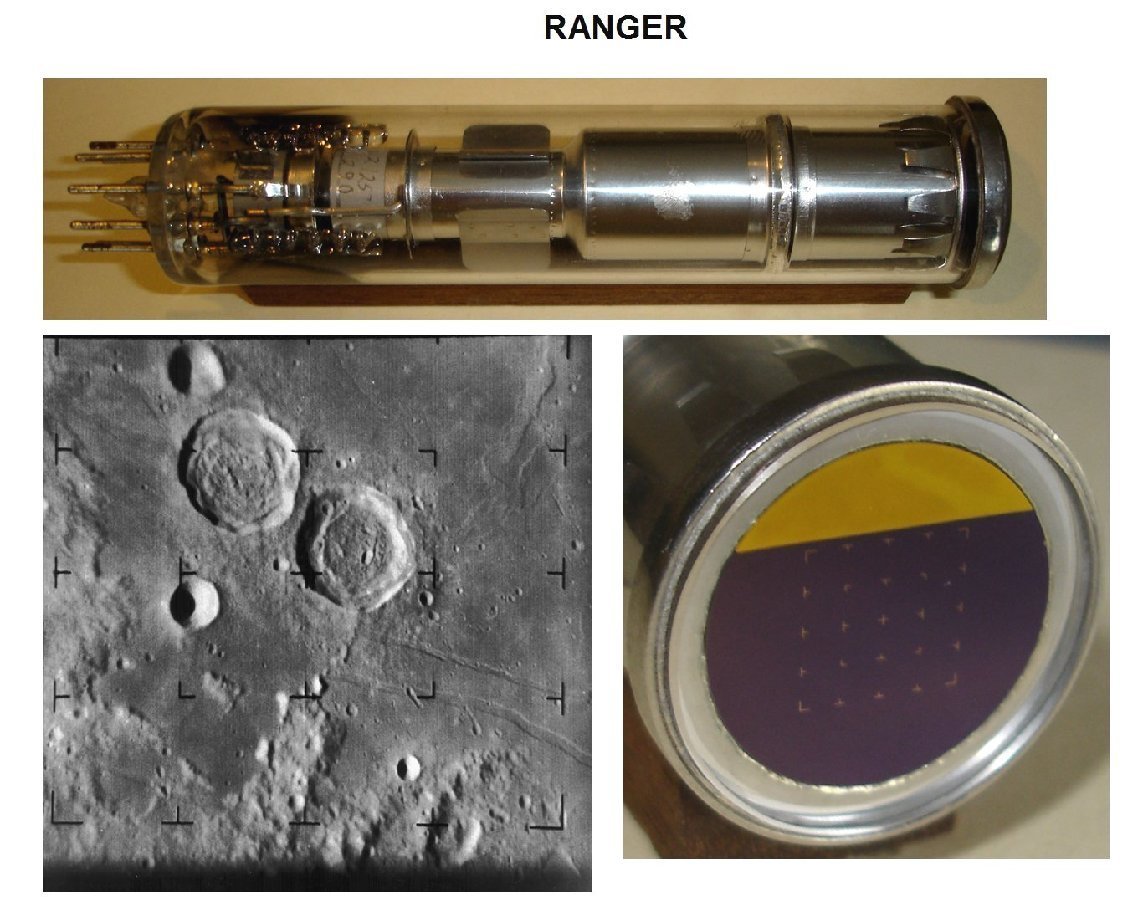

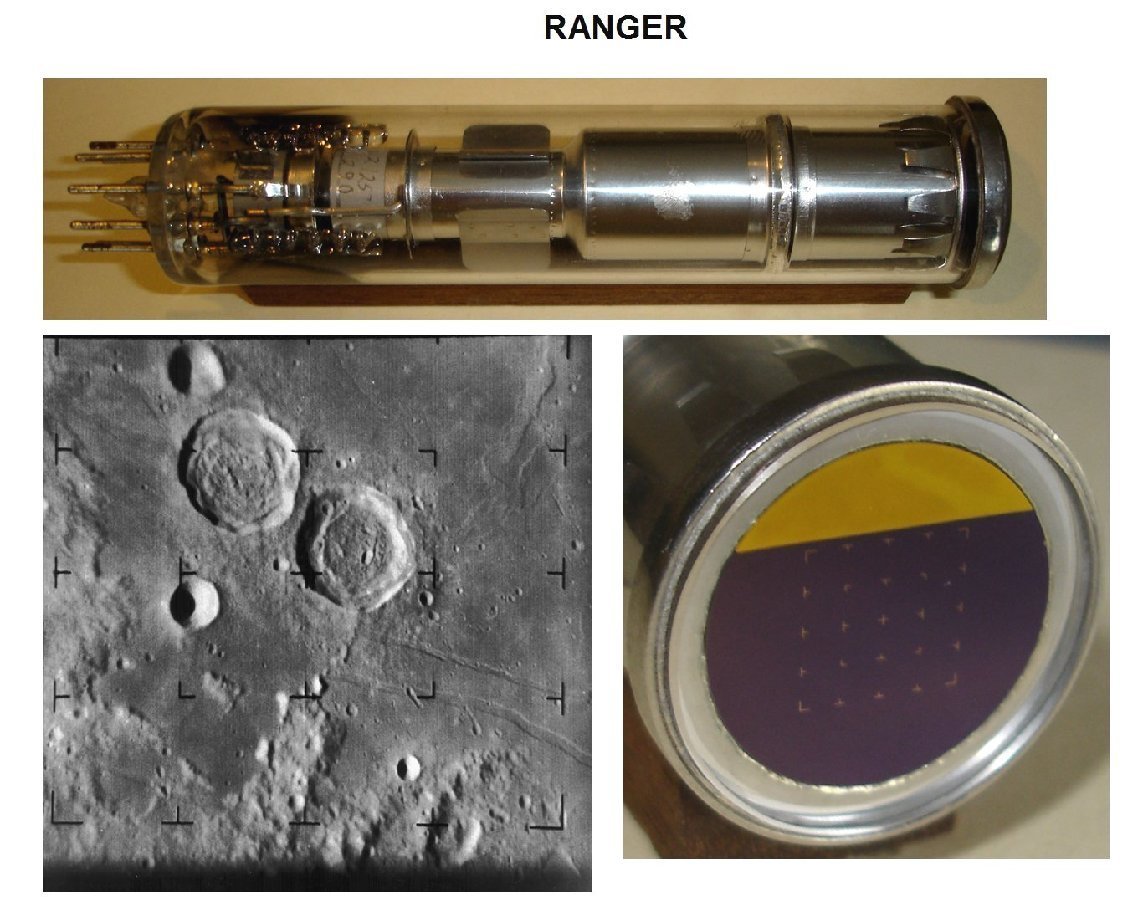

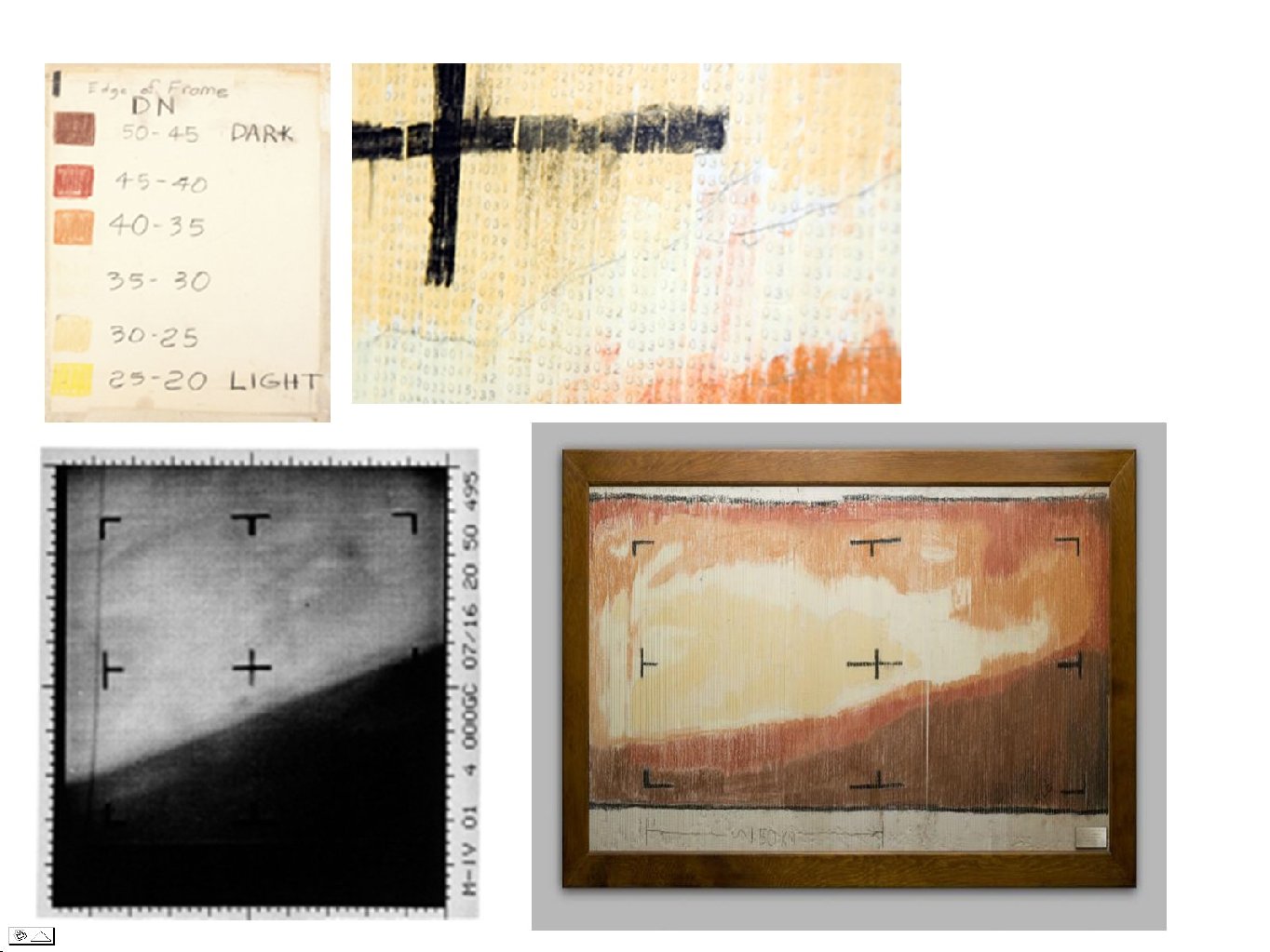

The Ranger program was a series of unmanned space missions by the

United States in the 1960s whose objective was to obtain the first

close-up images of the surface of the Moon. The Ranger spacecraft were

designed to take images of the lunar surface, transmitting those images

to Earth until the spacecraft were destroyed upon impact. Note

the alignment marks on the front of the tube match those on the

picture. These marks were different from mission to

mission, like a finger print. Vidicon tube photo

by James Janesick.

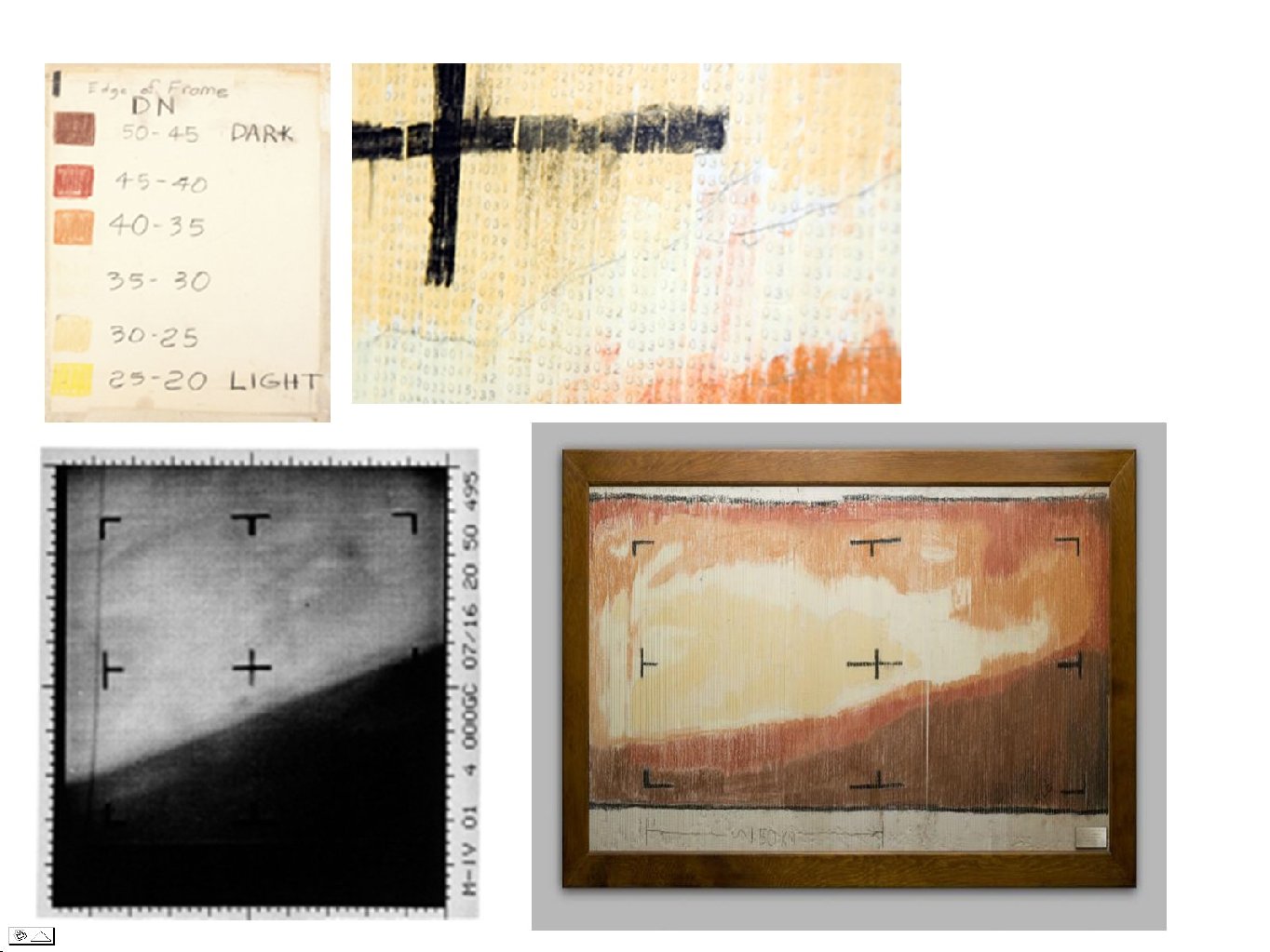

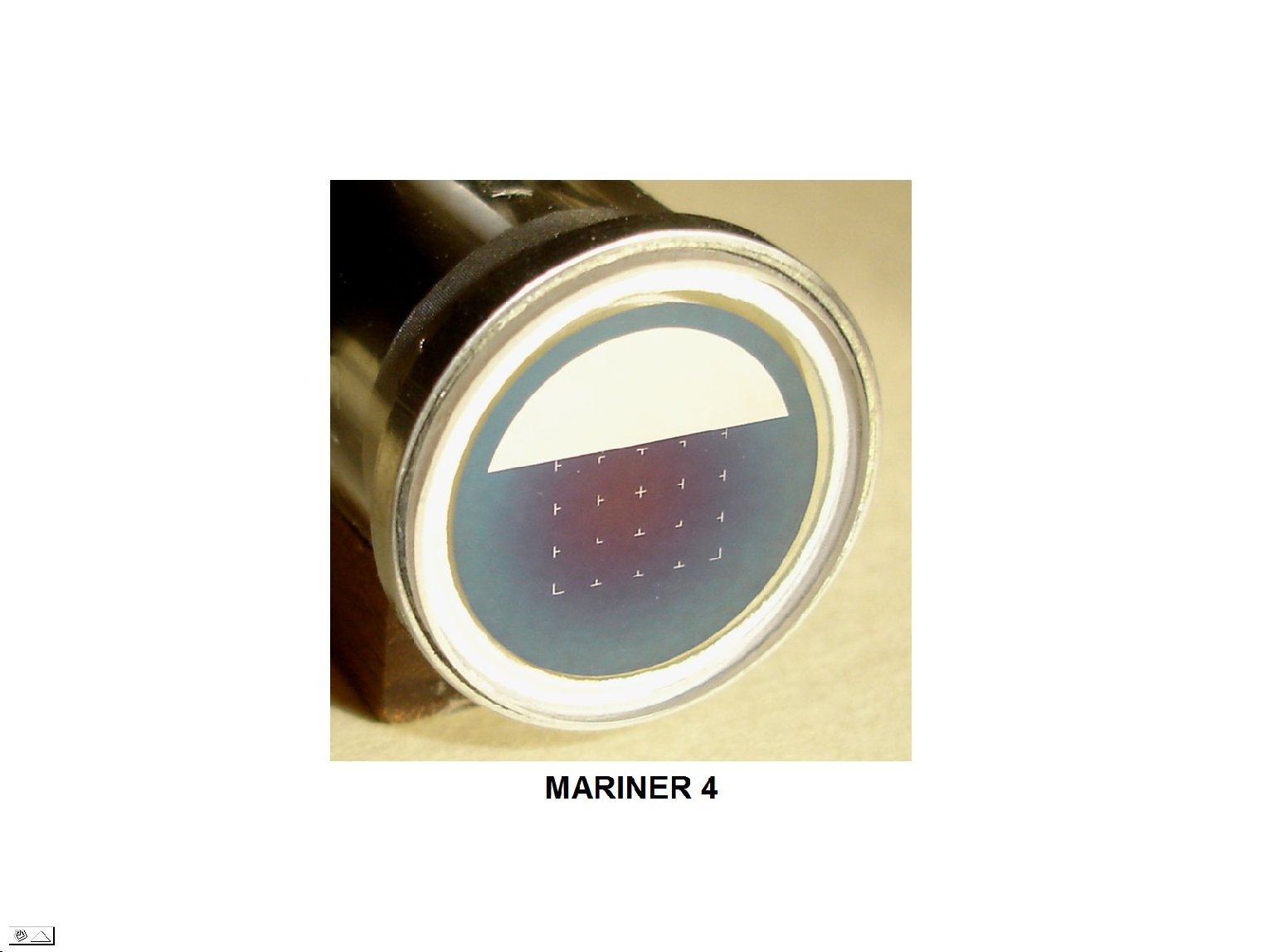

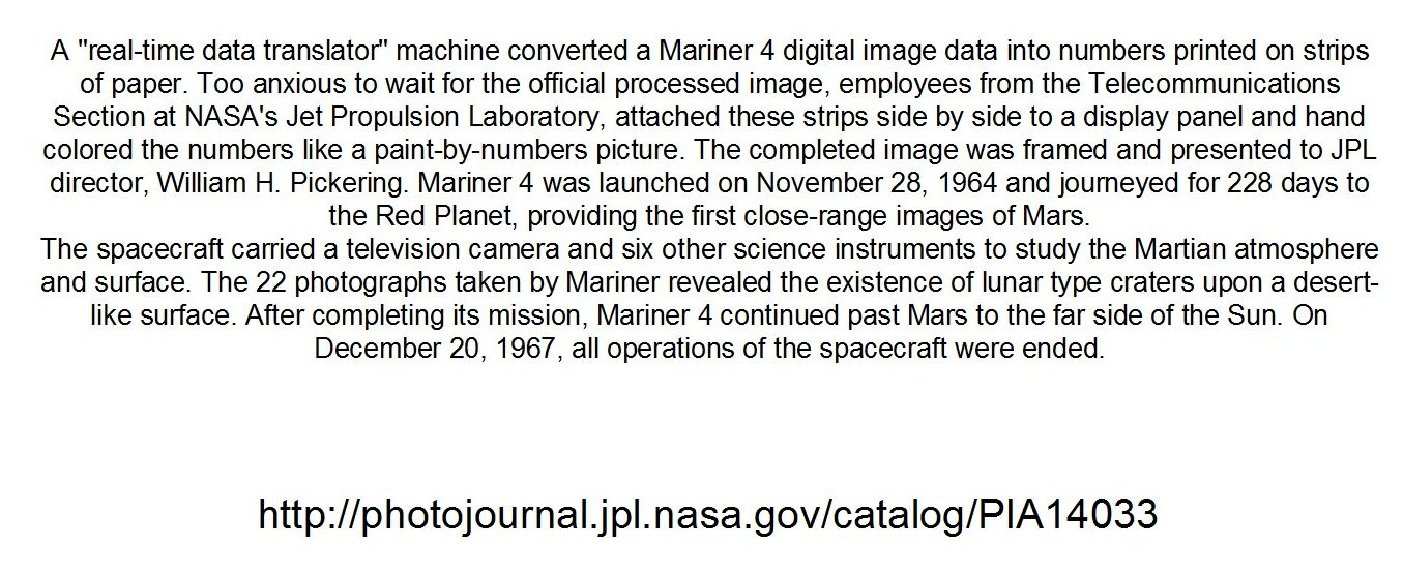

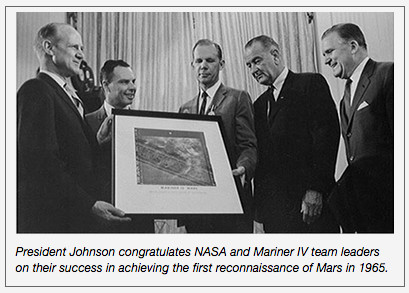

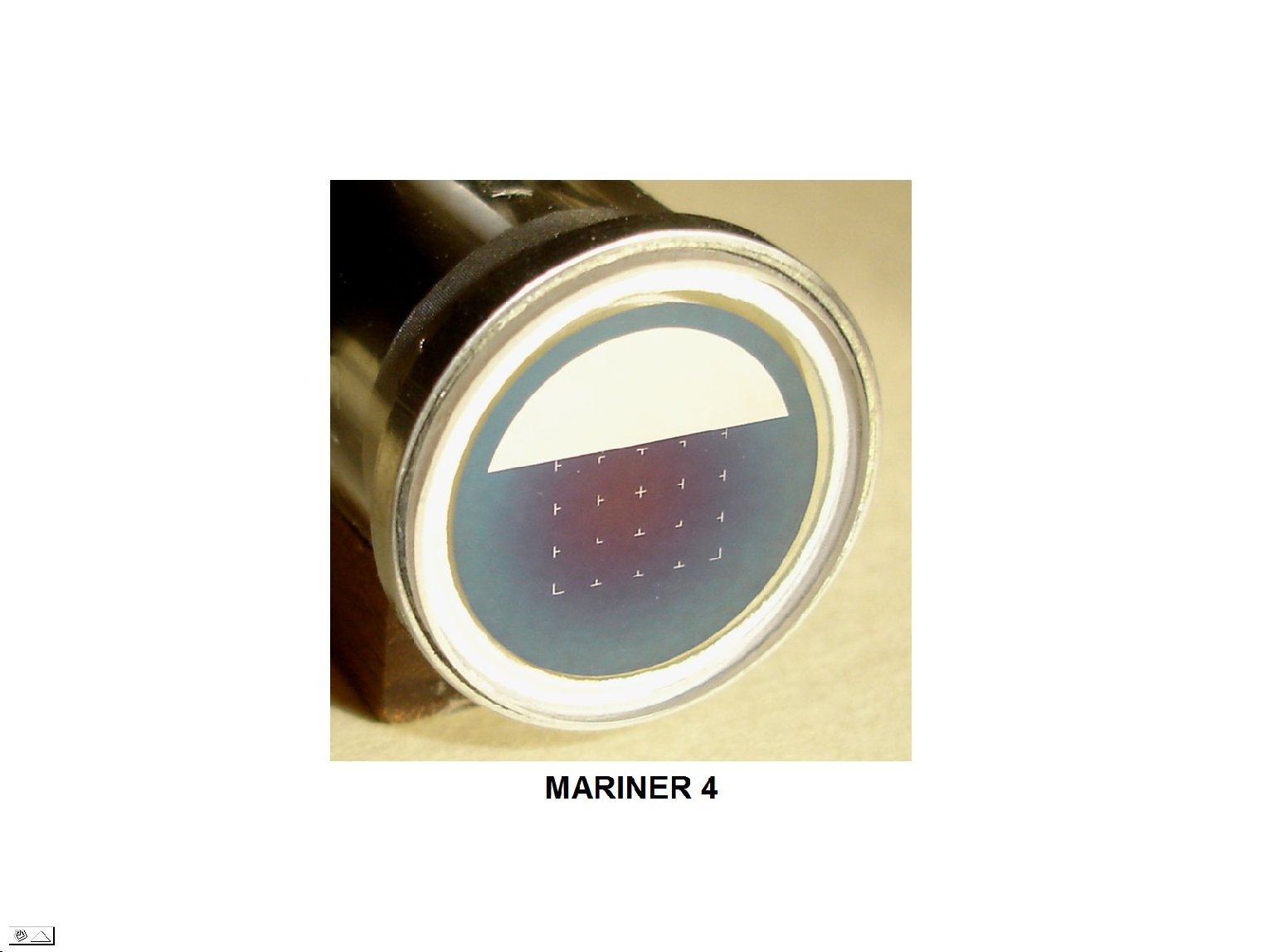

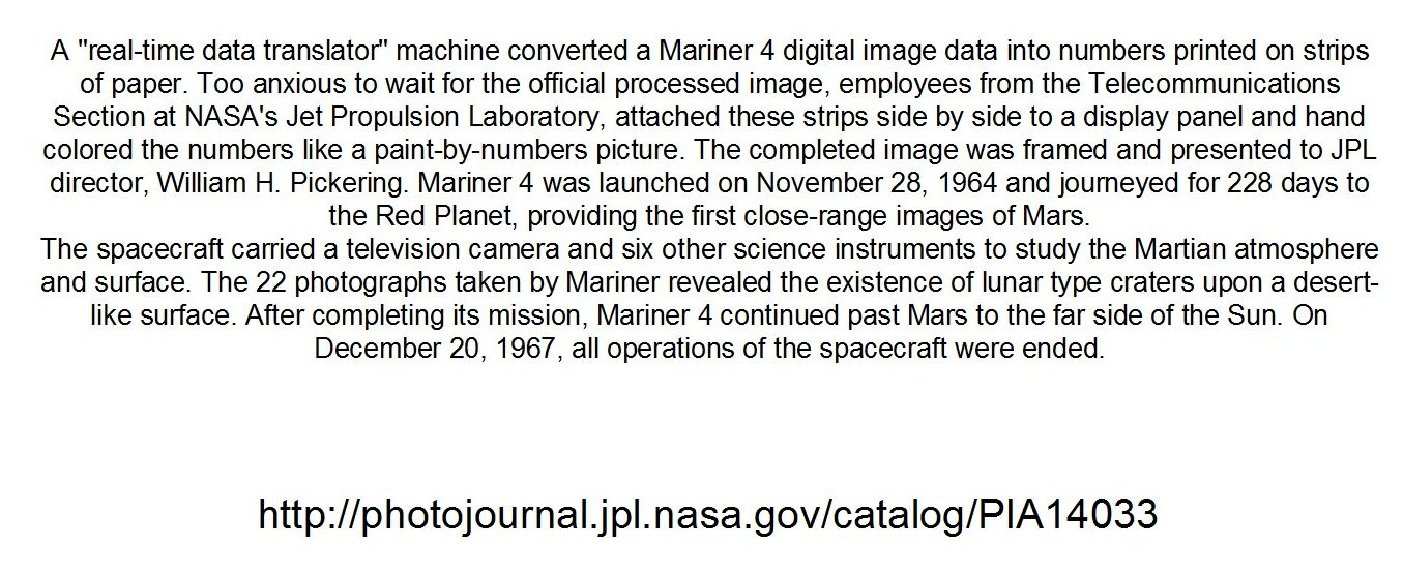

On the left Dr. Pickering, Directlor of JPL, center Jack James, Mariner 4

Project Manager, President Johnson second from the right.

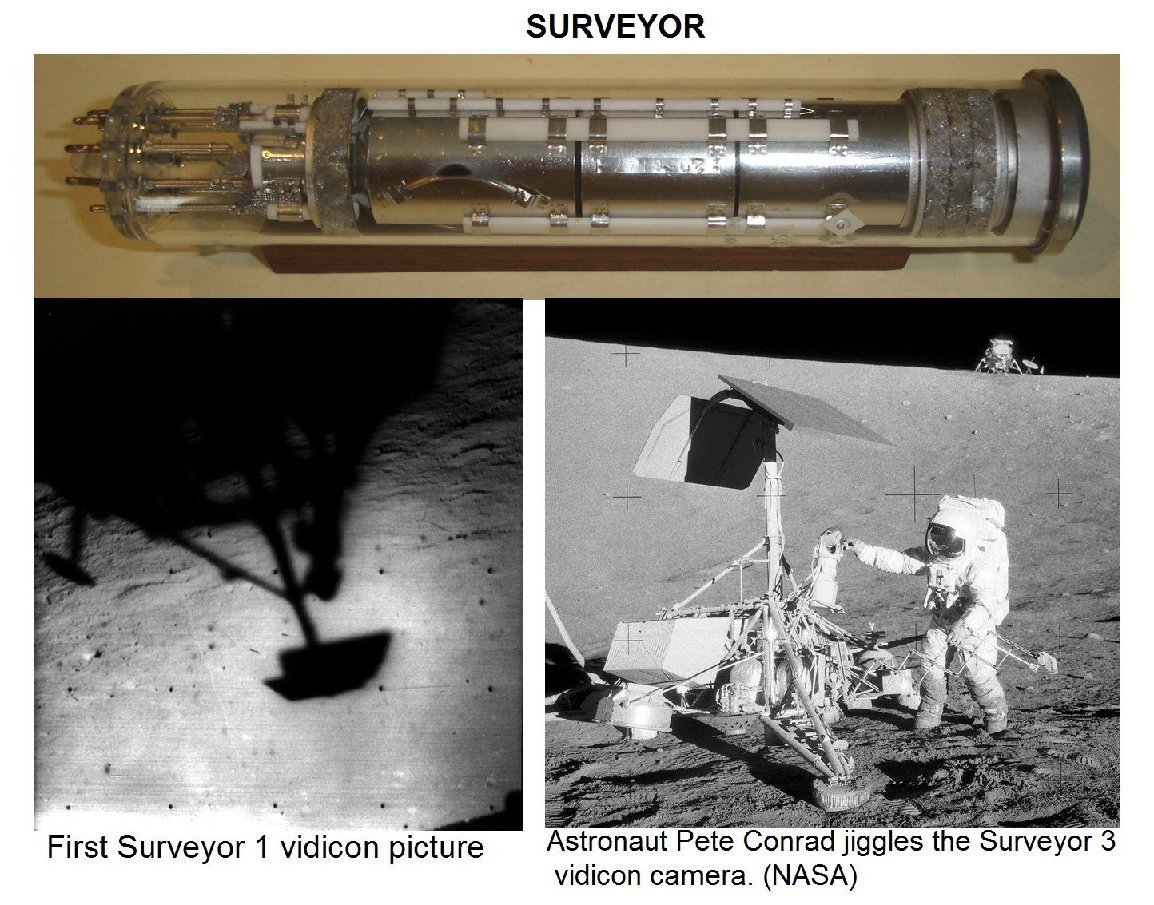

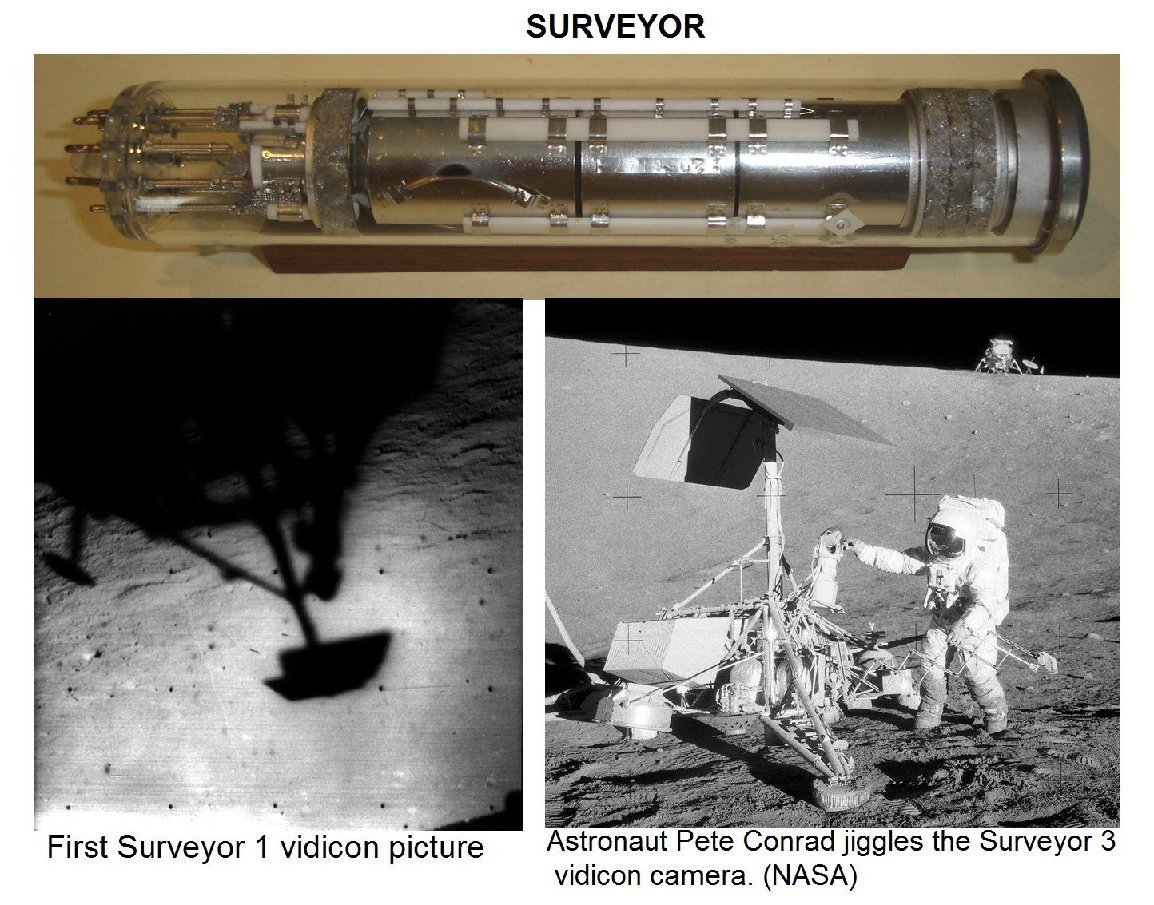

The Surveyor program was a NASA program that, from June, 1966 through

January, 1968, sent seven robotic spacecraft to the surface of the

Moon. Its primary goal was to demonstrate the feasibility of soft

landings on the Moon. The mission called for the craft to travel

directly to the Moon on an impact trajectory, on a journey that lasted

63 to 65 hours, and ended with a deceleration of just over three

minutes to a soft landing. The program was implemented by NASA's Jet

Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) to prepare for the Apollo program.

Vidicon tube photo by James Janesick.

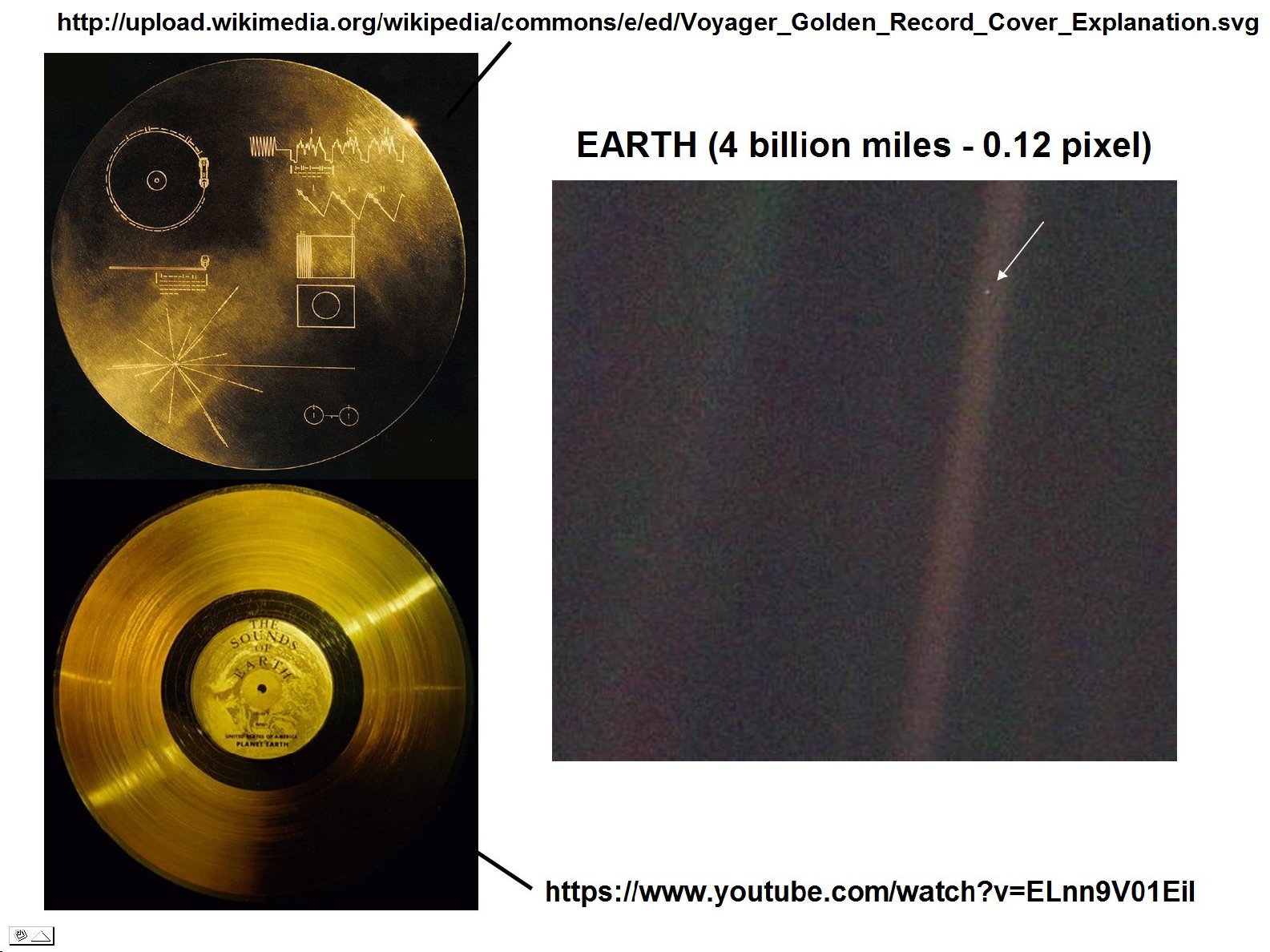

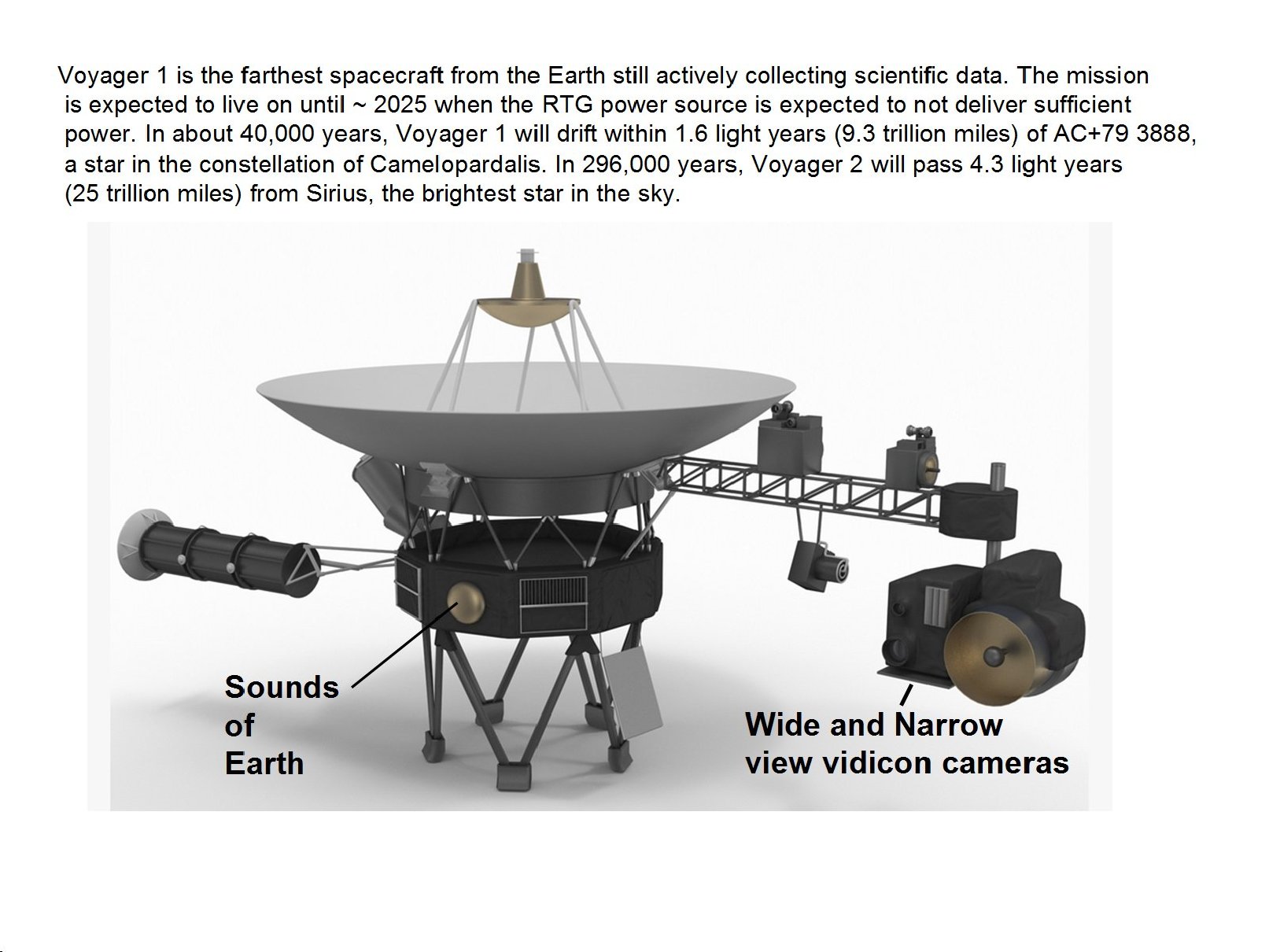

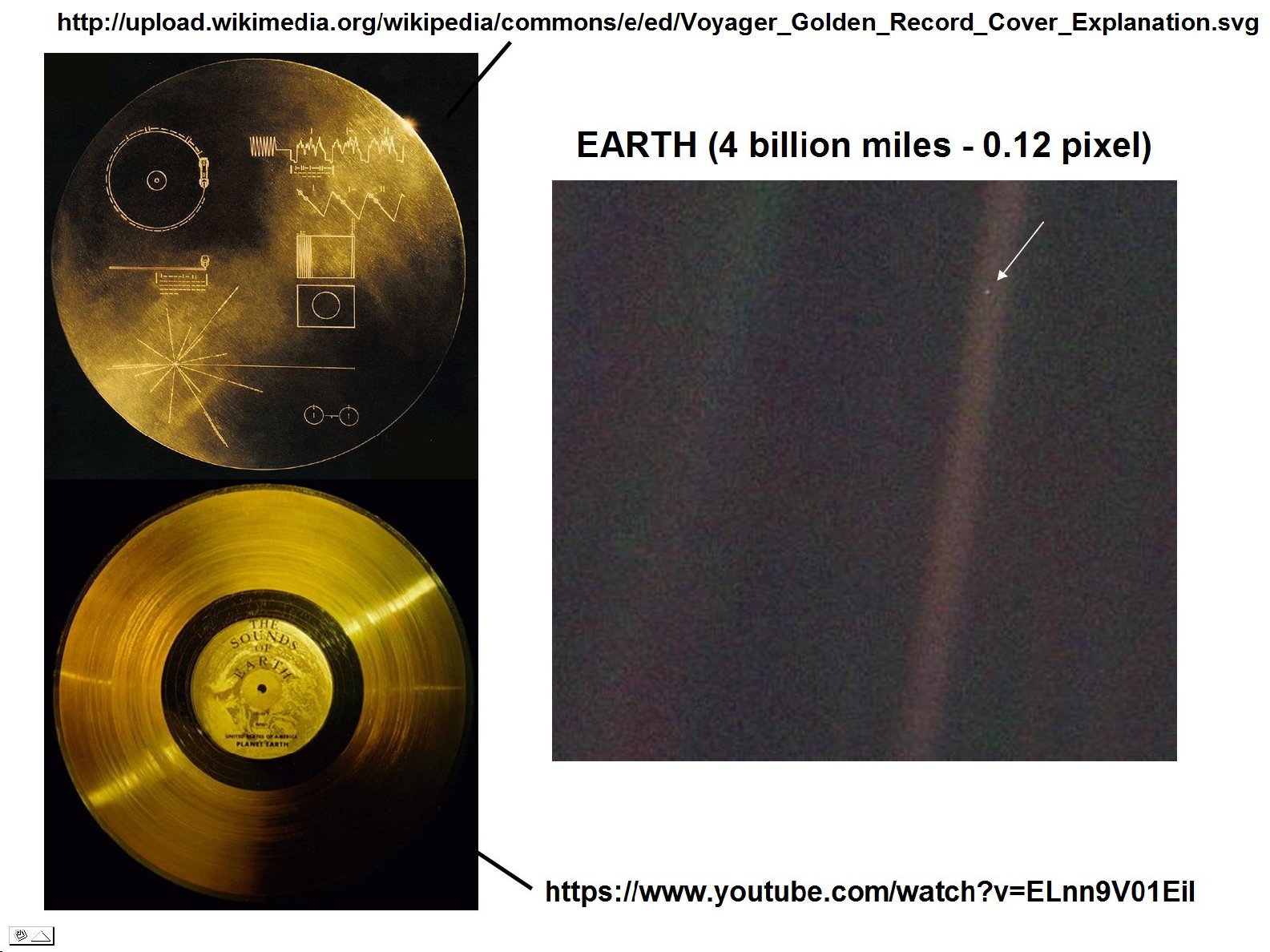

Explanation of diagrams on recording - http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ed/Voyager_Golden_Record_Cover_Explanation.svg

Voices and music recorded - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ELnn9V01EiI

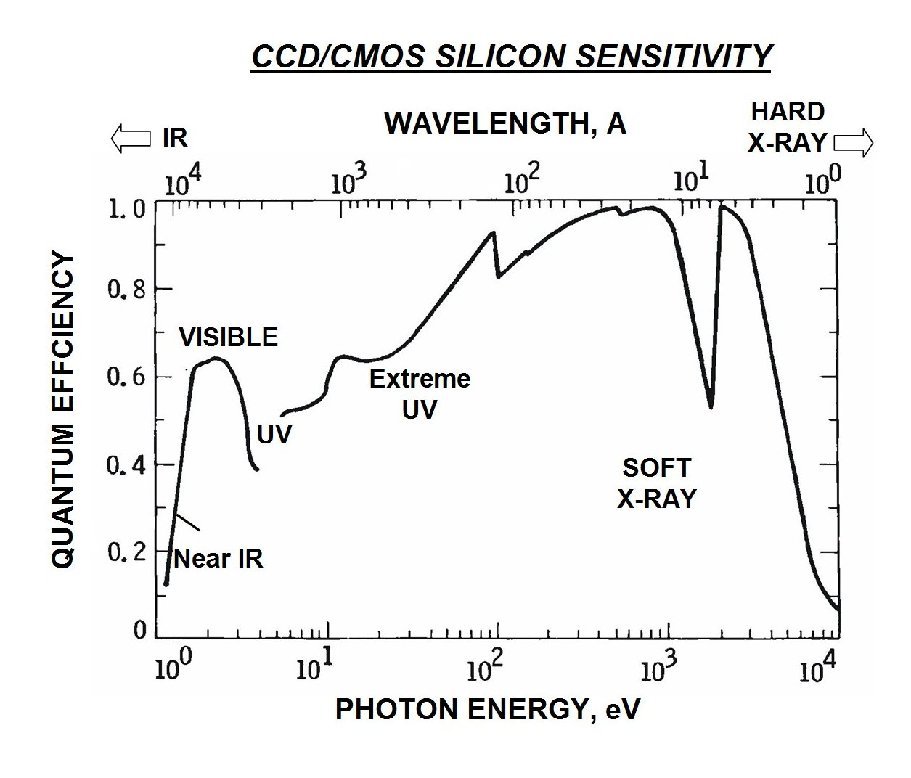

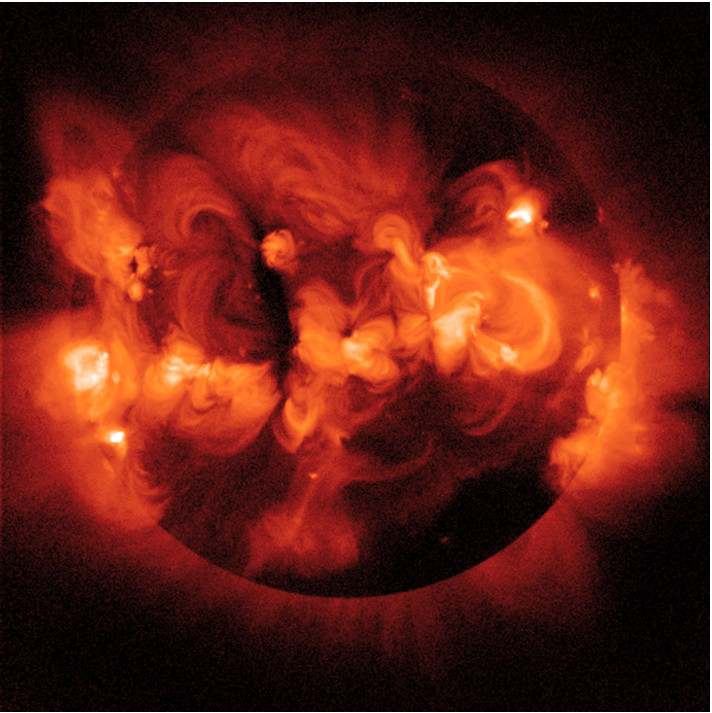

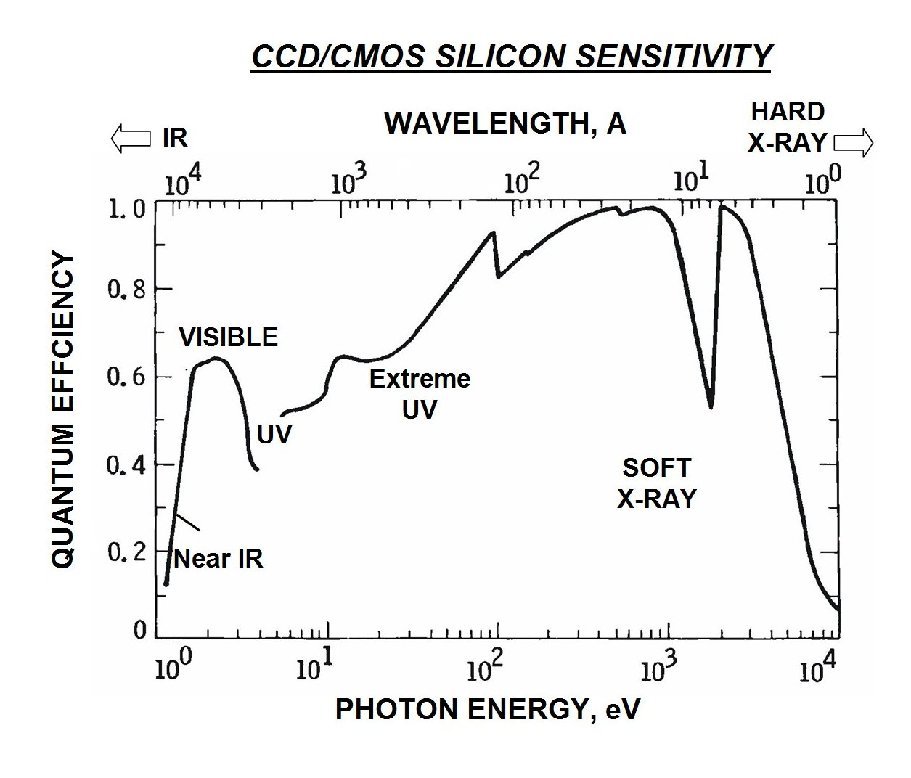

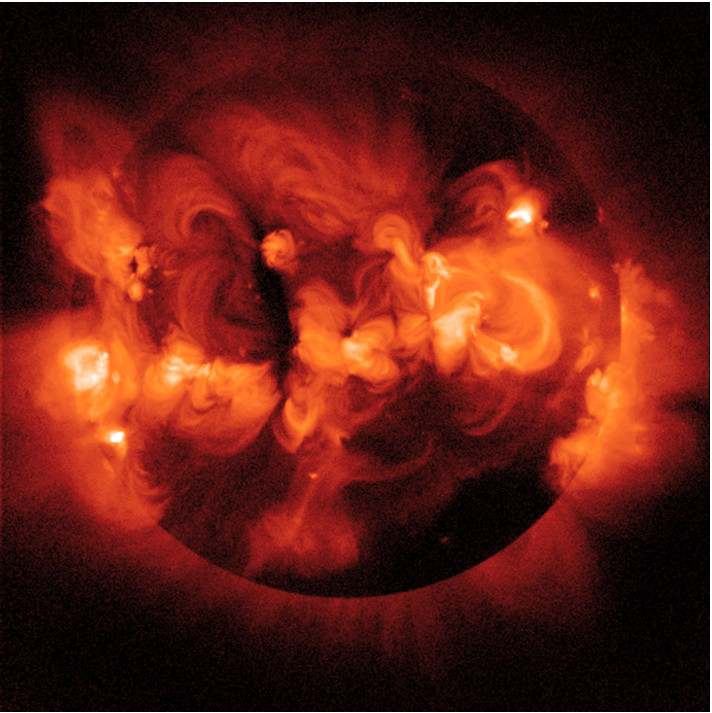

YOHKOH SOLAR X-RAY TELESCOPE (SXT) - 1991. The SXT was the first

X-ray camera launched into space. Janesick was involved with the SXT

mission

for five years and was responsible for the 1024 x 1024 x 18 um Virtual

Phase CCD flown as well as the associated analog electronics required

to read the device. Diagram

in the center illustrates the wide range of electromagnetic wave

sensitivity of CCD and CMOS imagers which makes them so valuable for

astronomical use in

addition to their extreme sensitivty to visiblel light. The photo

on the right is an X-ray image of the sun.

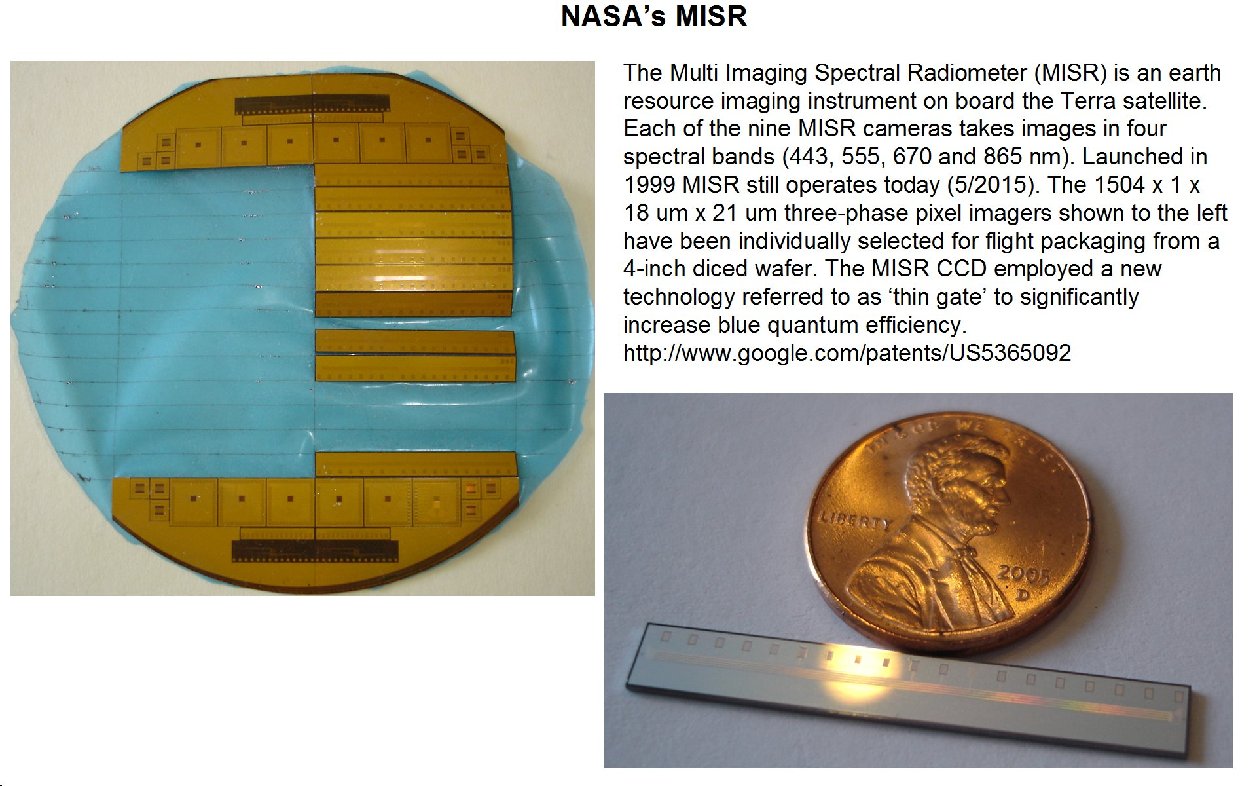

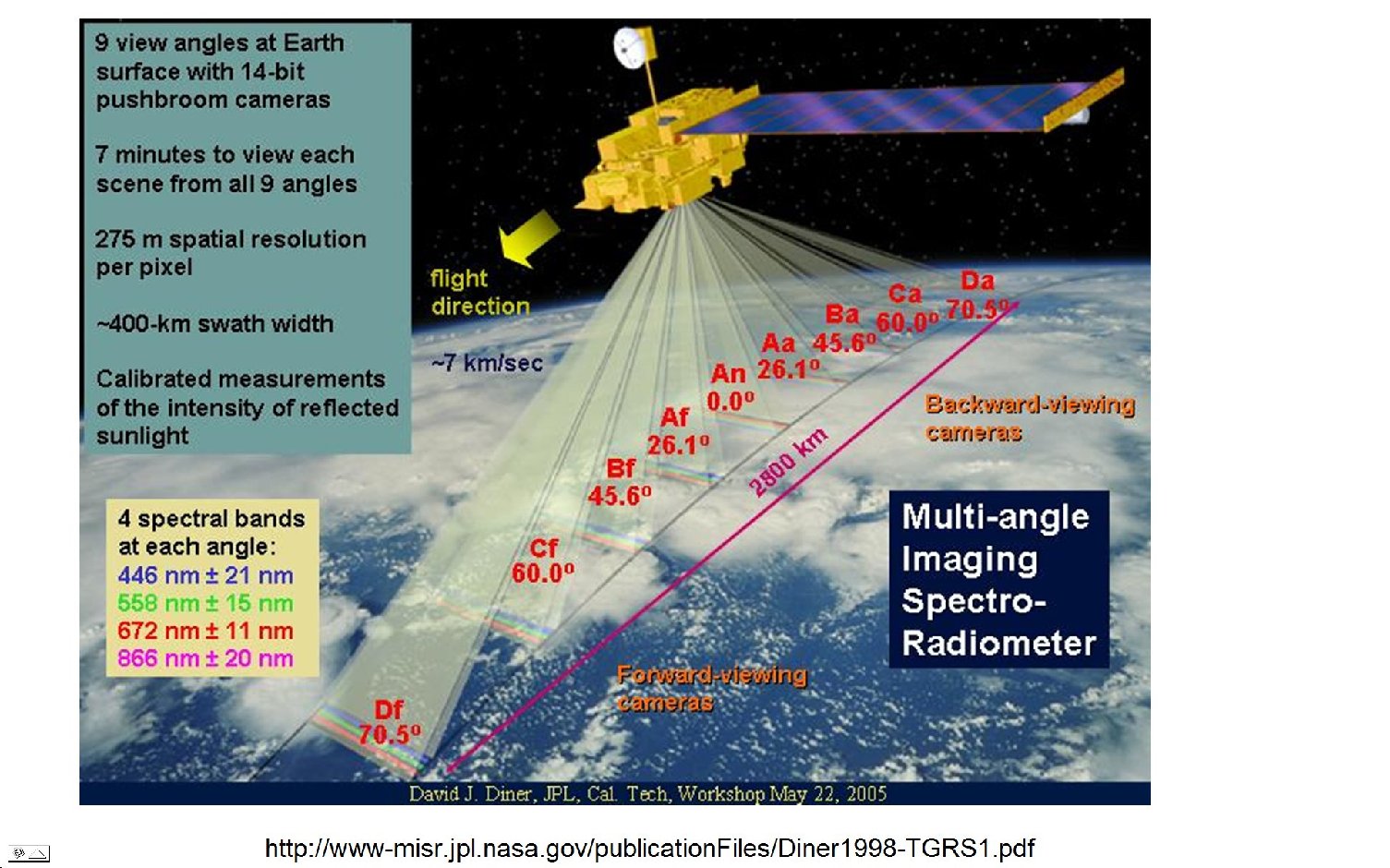

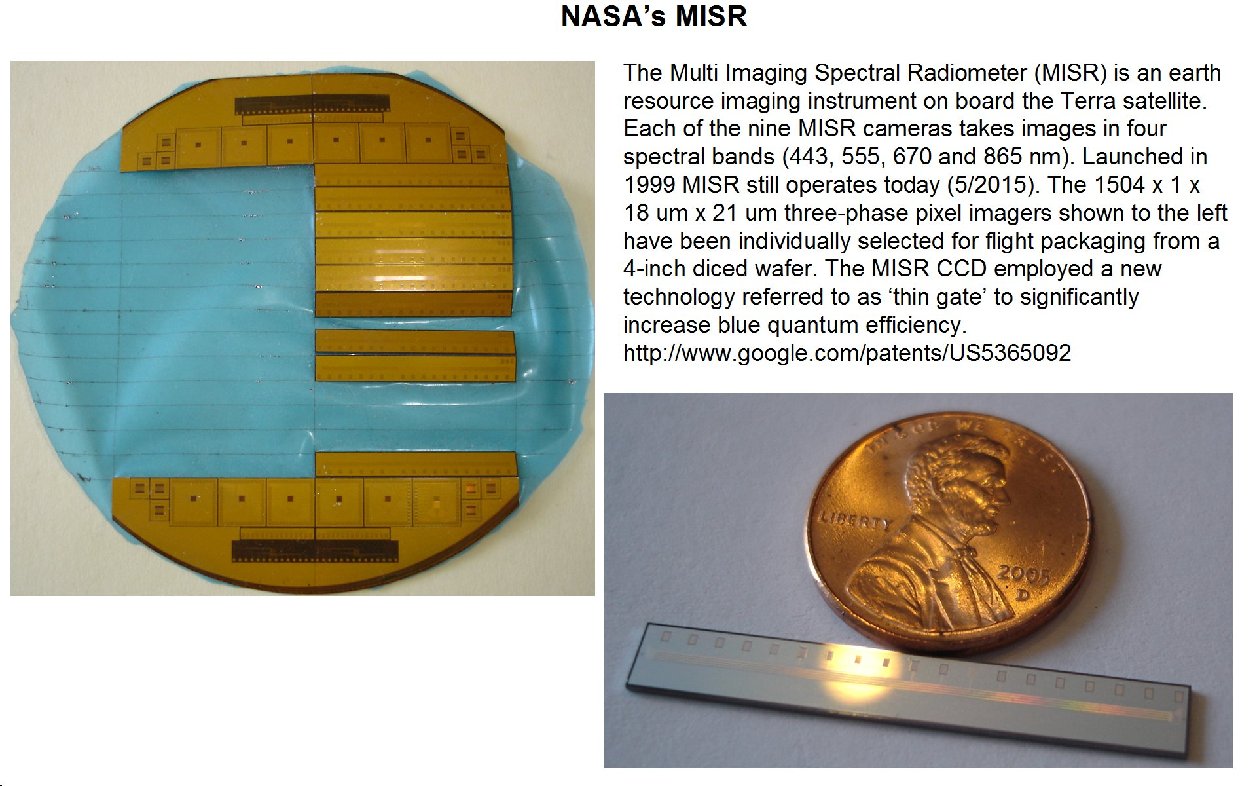

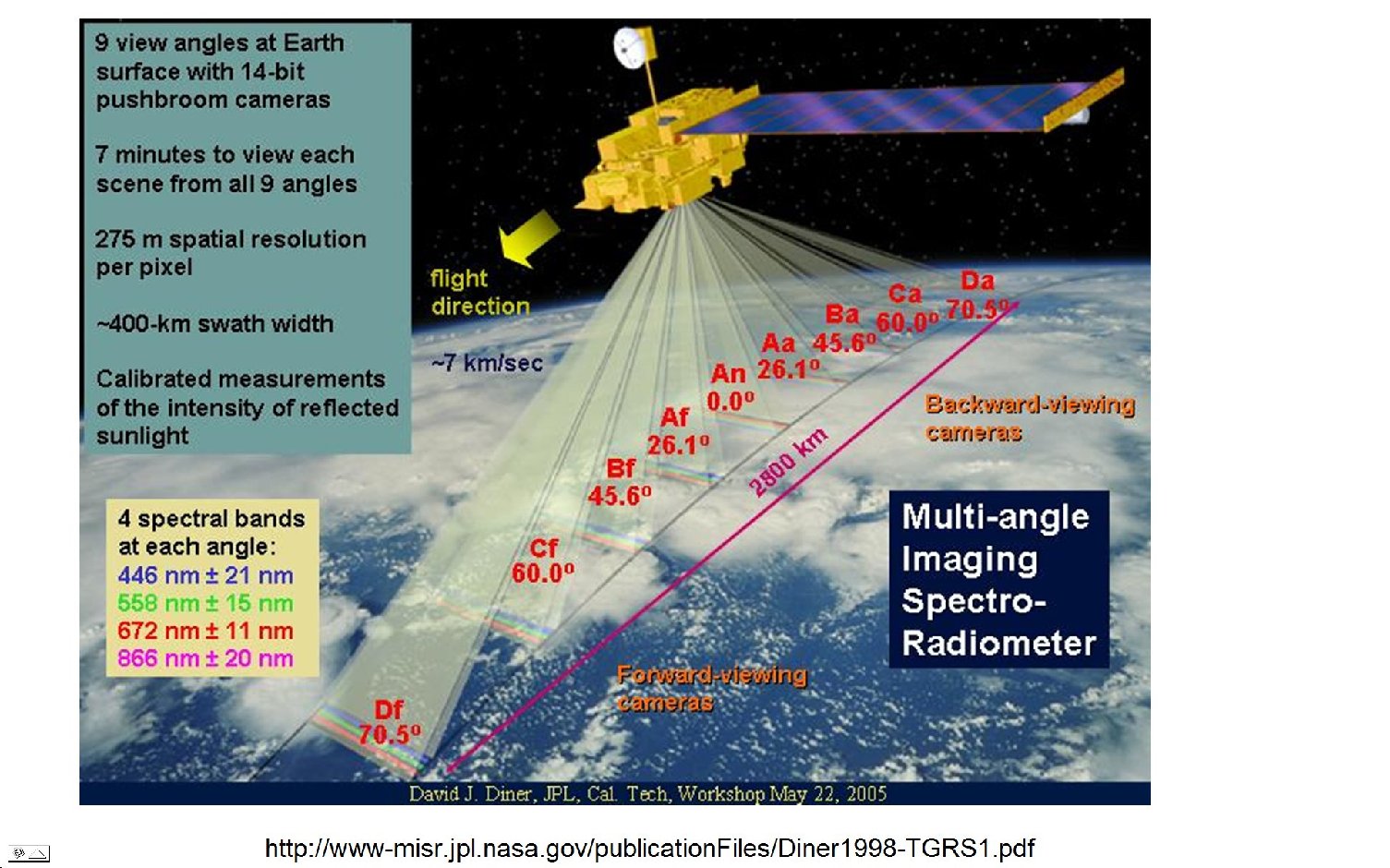

James R. Janesick CCD Patent information: http://www.google.com/patents/US5365092

MISR Information: http://www-misr.jpl.nasa.gov/publicationFiles/Diner1998-TGRS1.pdf

All above photos and information on this URL page provided by courtesty of James R. Janesick